Sacred Headwaters #50: The State of Mitigation (IPCC AR6 WG3)

We've known about climate change for a century and have been -- allegedly -- trying to prevent it for almost forty years. Have we made any progress?

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity, about the power structures blocking change, and about how we can overcome them and build a future in which all of humanity can thrive. If you’re just joining, consider checking out the first issue for some context and head over to our table of contents to browse the whole library. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but they do build on concepts over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Table of Contents

Sacred Headwaters has a table of contents intended to allow readers to “catch up” more effectively, facilitate using Sacred Headwaters as a reference, and give a better picture of what the newsletter is about for those who are just joining.

Issue #50: The State of Mitigation (IPCC AR6 WG3)

This is a brief interlude from the ongoing series on “TINA” (“There Is No Alternative”) which will return in the next issue.

I often assert in this newsletter (and other writing) that the world has made virtually no progress on climate change in the nearly 40 years since the international community decided to work towards slowing it. If anything, we’ve gone very far in the wrong direction (more than half of all anthropogenic emissions have been emitted since 1990). But this assertion is not necessarily broad consensus. After COP26, there was a rash of “good news” analyses arguing that we had come a long way on climate change because the “worst case scenarios” (or so-called “business as usual”) had moved closer to +3C by 2100, largely because of a faster than expected decline in the growth of coal use (not actual coal use). A decline that was not driven by climate policy, but by economics (and the rise of gas). Building on this story, a paper came out last week in Nature arguing that the net-zero commitments made at COP26 could keep 2100’s warming below +2C.

There are a few obvious problems with this good news story. First of all, net zero is decidedly not zero. The vast majority of net zero commitments are long term with no realistic short term goals. Many countries that do have shorter term targets and plausible mitigation policies are simultaneously pursuing fossil fuel expansion plans that make those targets impossible. There is very little evidence that we are actually making progress towards fulfilling these commitments and there is a mountain of evidence that many of the world’s worst offenders are doubling down on fossil fuel production.

Second, a “worst case scenario” of +3C (optimistic) is not that much of an improvement over the old “worst case scenarios.” Yes, the Earth system impacts are less horrific, but at some point we cross a social ecological threshold our society and structures won’t be able to withstand. Based on how we’re handling +1.2C, that threshold looks a lot lower than most “worst case warming” scenarios. The marginal differences for humans above that threshold — when cascading climate disaster-triggered, fossil-fueled nuclear war wipes us all out, for example — really aren’t something to celebrate.

Third, it paints a picture that suggests +2.5C would be “ok” in some sense — that it wouldn’t be a genocidal disaster unmatched by anything in human history. It’s worth remembering here that the target of +1.5C was not even in discussion among Global North countries before the Paris Agreement. Activists from the Global South (climate vulnerable countries) pushed hard, rightfully coining the phrase “1.5 to stay alive,” and ultimately transformed the global climate environment. That led the IPCC to produce the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 C which demonstrated that the differences between +2C (let alone +3C) and +1.5C for the Global South are massive. Suggesting that we’ve made progress when the outcome is still a virtually unliveable world for billions of people is carbon colonialism in action.'

Lastly, it’s problematic because it simply isn’t happening: atmospheric greenhouse gases are still rising at record rates! The atmosphere and Earth’s energy imbalance don’t care that certain nation states claim their emissions are going down. Even the “worst case scenario” estimates assume a gradual transition away from fossil fuels, something that countries are very clearly betting won’t happen. I’ll believe we’re making progress when I see it.

The IPCC released Working Group III’s contribution to its Sixth Assessment Report last week which focused specifically on mitigation, so I thought I’d take this opportunity to dive into the state of mitigation a little more deeply and document the nearly half century failure of domestic and international climate policy. We’ll read an excerpt from the new report as well as some other work on the state of emissions today.

I hope it’s clear that I’m not writing this issue to dispel hope. I’m writing it to dispel greenwashing and encourage people to think — and demand — bigger. As the report’s Technical Summary puts it,

Meeting the long-term temperature goal in the Paris Agreement…implies a rapid inflection in GHG emission trends and accelerating decline towards ‘net zero’.

This is implausible without urgent and ambitious action at all scales (p. 5)

We have an accelerating rise of net zero commitments…but no actual “decline towards ‘net zero.’” The widespread emphasis on meaningless long-term commitments — and the associated “good news” narrative-building — is serving primarily to legitimate the status quo, rendering real decline in emissions more and more “implausible.” Our approach needs to change.

Technical Summary in: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (IPCC AR6 WGIII) (45 minutes)

Feel free to read the whole thing, but if you don’t have time for the whole 145 pages, sections 1, 2, and 3 really get at what we’re discussing in this issue. If you’re wondering about the watermark that says “Do not Cite, Quote or Distribute,” the IPCC has authorized publication and distribution now, they just haven’t finalized and published the long term version (pending copy-editing and layout).

This report is packed full of good stuff (and you may notice it draws from many of the diverse topics and authors we’ve explored in this newsletter). I really recommend reading at least the first few sections and I won’t attempt to summarize it here, though I will pull out a few highlights. Table TS.1 sticks out in our context as it lists “signs of progress” next to accompanying “continuing challenges.” The continuing challenges really temper the signs of progress. For example, the table points out that while EV adoption is occurring rapidly, overall transport emissions continue to rise due to (among other things) “heavier vehicles” (SUVs) and “car-centric development.” It also briefly mentions the need for EV adoption to be accompanied by decarbonization of both energy production and the entire EV supply chain, the latter of which is often swept under the rug. Another interesting entry in the table was that more and more state and non-state actors are actively involved in climate policy…but the authors cautioned that “there is no conclusive evidence that an increase in engagement results in overall pro-mitigation outcomes,” citing disinformation campaigns by “climate change counter-movements” (aka fossil fuel and capital interests) as a reason for that.

Section TS. 3 discusses emissions trends. These are the numbers that are most important when you ask, “Are we making progress on climate change?” And they yield an unequivocal “No.” Emissions from 2010-2019 were higher than ever, and the amount emitted during that period was roughly equivalent to the remaining “carbon budget” for +1.5C. Which means, now that it is 2022 and emissions are continuing to grow, we’ll blow past that budget within a few years. It’s generally agreed now that we’ll blow past the actual temperature within a decade or so. The authors also note that a small handful of countries appear to have decoupled GDP growth from emissions, but that the majority of countries that are seeing emissions reductions are actually just exporting those emissions through trade (what I called “carbon outsourcing” in issue #45).

There’s a lot in here and it really doesn’t pull its punches; highly recommend making the time to read at least the first few sections.

Current national pledges under the Paris Agreement are insufficient to limit warming to 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot, and would require an abrupt acceleration of mitigation efforts after 2030 to likely limit warming to 2°C (p. 11).

As a sidenote, you may have heard that the WGIII report was delayed because of political negotiations. Basically, every member country’s delegation has to approve the report’s Summary for Policy Makers. In other words, Saudi Arabia, the US, Canada, etc. — the world’s oil producers — get to decide how the IPCC’s reports on climate change are summarized. As such, the Summary for Policy Makers is not reflective of the underlying scientific consensus, but the rest of the report remains mostly uncompromised.

Increase in atmospheric methane set another record during 2021 (5 minutes)

NOAA, April 7th, 2022

This news release summarizes NOAA’s latest findings on atmospheric methane and CO2 levels. As mentioned above, and in the IPCC report, the findings are not good. The release quotes a number of NOAA scientists who put it rather straightforwardly:

Our data show that global emissions continue to move in the wrong direction at a rapid pace. The evidence is consistent, alarming and undeniable.

It also situates these atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations within paleoclimate data which offers some perspective on just how much the world’s wealthy have screwed things up. The last time atmospheric carbon was at this level was 4.3 million years ago! Sea level was 75 feet higher and average temperature was almost 4C higher. The Atlantic ran a spectacular piece by Peter Brannen on paleoclimate data and climate change last year that’s well worth a read.

The accelerating rise of methane emissions over the last decade is particularly notable for two reasons. First, scientists are getting better and better at figuring out where it’s coming from, and it turns out much of it is coming from the fossil gas boom (so-called “natural gas”). Gas is methane. When they drill for it, it leaks. When they pipe it, it leaks. When they burn it, it leaks. And obviously enough, when they abandon wells, it leaks. Building more gas infrastructure means locking in still more methane emissions.

Second, methane leaks as a byproduct during oil extraction. In many cases, it’s even purposefully “flared,” or burned off on site (despite being a marketable commodity). The interesting piece here is that studies have demonstrated (for over a decade now!) that a large portion of oil industry methane emissions could be eliminated with existing technology at low or no cost through the implementation of fairly simple regulations. And yet…methane emissions are higher than ever before.

Debunking Demand (IPCC Mitigation Report, Part 1) (10 minutes)

Amy Westervelt, Drilled News, April 5th, 2022

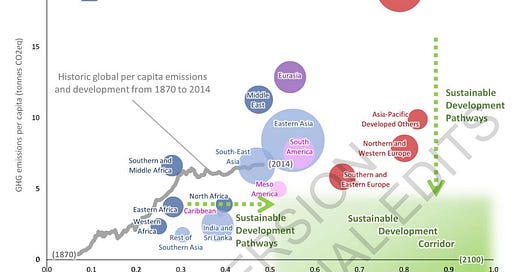

Westervelt is producing a series on the IPCC report and in this entry, brings up something that I’m hoping can serve as a bit of its own “good news” end to this newsletter issue. If you’ve already read the first few chapters of the Technical Summary, you’ll have seen that it talks a bit about the plausibility of absolute decoupling of emissions and GDP. The experience of some countries suggests that this may be possible…but the fact that global carbon intensity of energy production has been declining (good) at a rate of 0.3% a year (bad) suggests that we are out of time for seeing decoupling as our primary path forward. Which is why what Westervelt writes about here — Chapter 5 of the report — is so important. The IPCC authors essentially argue that traditional economic growth should no longer be the metric by which we pursue sustainable development — that a focus on the actual services people need to improve their living standards has the potential to be both more effective and more compatible with climate mitigation than a focus on economic growth more broadly. This is a core tenet of degrowth economics (issue #7) and doughnut economics (issue #2) and it is a revolutionary departure from the prevailing economic theory of development of the 20th century: “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

Westervelt talked to one of the report’s authors, Dr. Julia Steinberger (who’s work has been featured in a number of issues of this newsletter), who made this key point:

One of the myths [about the economy] is that it's demand driven when it's not. It's supply driven.

This is something I really try to elucidate in this newsletter. It's a critical point about understanding how our economy has baked in overproduction and how capitalist, market-driven approaches to resolving the climate crisis actually just entrench it. EVs are a great example — our approach to electrifying transport, at least in certain Global North countries, has been to hand already well-off people a bunch of money to buy more products that are just marginally less bad. Great for capital. Bad for the planet and the rest of us.

This section of the report demonstrates that social science consensus has shifted dramatically over the last few years. Its key takeaway is that we could meet the world’s needs (which aren’t being met today) at half of current total energy use. The rest of the report makes the case that we must.

Like what you’re reading here?

Sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue and consider forwarding this email to a friend or colleague.

Hey Nick, congrats and thanks on the 50th Sacred Headwaters. I can't believe the amount of work you put in there. Great work, extremely interesting from the start. You covered such a broad range of subjects and dived deep into social and economics issues that are imo the real cause of climate change and is often avoid by more mainstream climate groups. Great work. And by the way, what are we gonna do without you in Squamish?

How is it that a country's carbon emissions don't include that of its military? This is definitely a form of green-washing by using commodities like EVs to the population while belching carbon from the war machines.