Sacred Headwaters #45: Carbon Colonialism Pt 4 – Carbon Outsourcing

Many countries of the global north have reduced their territorial emissions over the last decade or more. But are they actually just passing those emissions to the south by outsourcing production?

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and head over to our table of contents to browse the whole library. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Table of Contents

Sacred Headwaters has a rudimentary table of contents intended to allow readers to “catch up” more effectively, facilitate using Sacred Headwaters as a reference, and give a better picture of what the newsletter is about for those who are just joining.

Issue #45: Carbon Colonialism Pt 4 - Carbon Outsourcing

This is the last issue of four on “carbon colonialism.” In this series, we’re looking at the unequal distribution of culpability for climate change, both historically and in the present. We’re also looking at how the climate crisis is being exploited to develop new forms of colonial relationships between the north and south.

Issue #42: Carbon Colonialism Pt 1 - Historical Emissions (Nov 29th, 2021)

Issue #43: Carbon Colonialism Pt 2 - Carbon Inequality (Dec 13th, 2021)

Issue #44: Carbon Colonialism Pt 3 - Carbon Markets (Jan 9th, 2022)

Issue #45: Carbon Colonialism Pt 4 - Carbon Outsourcing (Jan 23rd, 2022)

There’s a dubious economic concept known as the Kuznets curve that argues as countries “develop” – as GDP per capita increases – inequality will first rise, then fall. Putting aside the rather blatant empirical falsehood of this relation today, I bring it up because there is an equally dubious analogous concept know as the environmental Kuznets curve: the idea is that as GDP increases, environmental harm will grow to a point, then begin to fall.

The flaws of the environmental Kuznets curve are not quite as painfully obvious. Proponents point towards a variety of environmental metrics such as air quality, environmental pollutants, and even carbon emissions, arguing that developed countries have now decoupled economic growth from environmental degradation broadly or from emissions specifically.

The problem is that the time period over which the environmental Kuznets curve seems to capture certain processes accurately – as the global north deindustrialized in the latter half (particularly, the final quarter) of the 20th century – is the same time period during which globalization and global trade exploded. The rise of global trade and the increasingly free movement of capital around the world allowed production to move wherever it was cheapest, a metric dictated by things like labor costs, governance, and environmental regulation.

In other words, as the north regulated (certain) environmental pollutants, much of its production was offshored in what amounts to a monumental act of cross-border environmental racism, driving the rise of air pollution and other harmful problems in the global south.

It turns out that this same process of deindustrialization that “cleaned up” production in the north (by moving it out of sight) is also obscuring the reality of progress on emissions reductions and, in turn, driving intensely colonial and unjust dynamics in international climate negotiations.

Emissions reductions are typically talked about within a framework known as “methodological nationalism:” each country’s emissions targets (whether the newer round of vague long-term net zero targets or the more concrete targets of the Kyoto Protocol) are focused on reducing emissions within their own borders – territorial emissions. But with international trade in the picture, this misses an entire piece of the puzzle.

As the UK, EU, and even the US have lowered emissions, their imported emissions (also known as consumption emissions) have grown, in many cases by roughly the same amount as their territorial emissions have decreased. The UK is perhaps the most emblematic example because it is one of the only nations to consistently hit climate targets (which it’s been setting since 2008): the majority of their emissions reductions have been offset by increasing embodied carbon in imported products. In other words, UK consumption is causing the emission of nearly the same amount of carbon as it used to, but countries in the global south are bearing the blame.

This is problematic in two ways: first, it calls into question the plausibility of lowering global emissions at all using national climate targets. But second, it makes the colonialism of international climate politics that much clearer. Not only are those historically most culpable for the climate crisis asking poorer countries to bear the brunt of the crisis itself and the economic impacts of decarbonizing quickly…but they are also using methodological nationalism to shift the blame for their own continued unsustainable levels of consumption to poorer countries.

In this issue, we’ll read about the scope of carbon outsourcing and the mechanisms by which it operates; how this process creates a veneer of progress; and some of the approaches being considered to deal with it.

The Carbon Loophole in Climate Policy (40 minutes)

Daniel Moran and Ali Hasanbeigi, ClimateWorks, 2018

If you’re in a rush, you might read Brad Plumer’s article in The New York Times about this report instead or as a starting point.

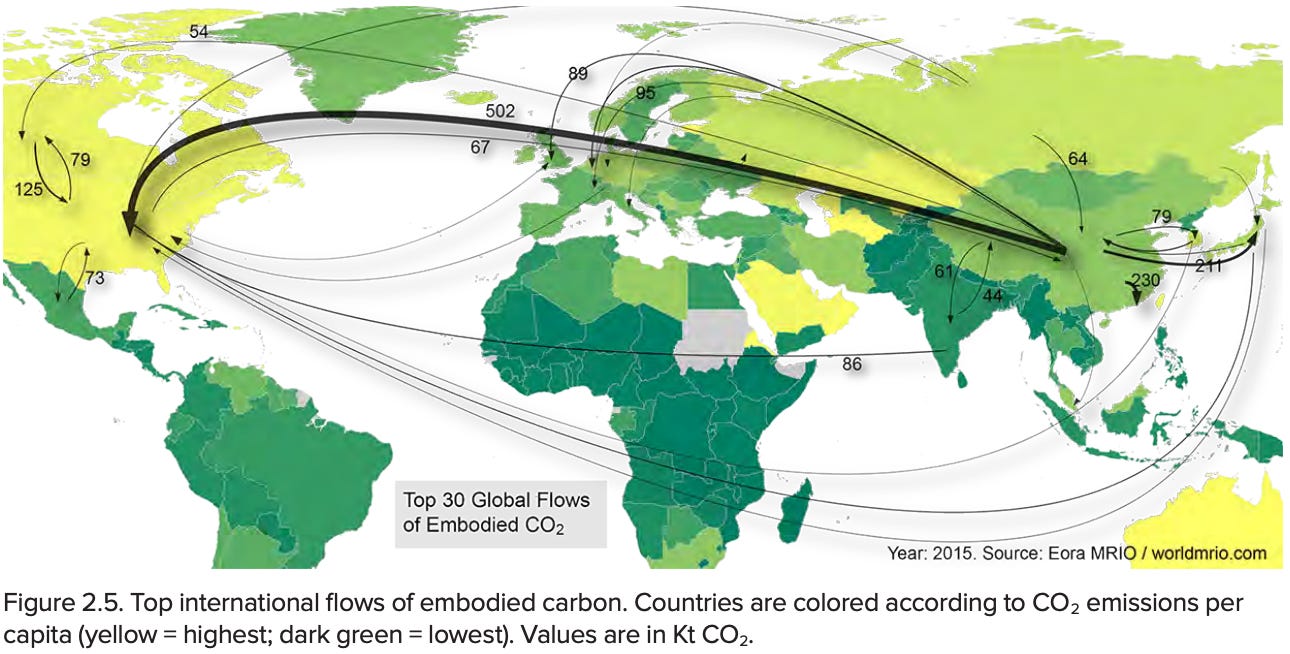

This report delves into the problem of carbon outsourcing – the authors call it the “carbon loophole” – and uses the latest data available (2015 at the time) to quantify its scale and relate it to ongoing developments in global trade patterns. A full 25% of global CO2 emissions are “embodied in imported goods.” In other words, 25% of global emissions are being produced in places removed from the consumption that is driving those emissions. Embodied and imported emissions grew steadily throughout the period of intensifying globalization, plateauing as a result of the 2008 global financial crisis. They have largely stayed static in total since then, though their distribution is changing as countries like China begin to deindustrialize: what the authors call “south-south” trade is increasing the amount of emissions transfer between countries of the global south.

The report compares this carbon trade with stated northern emissions reductions, as I alluded to earlier, and the results are grim: if you account for emissions outsourcing, most of the progress northern countries have made (excluding, of course, Canada, the only G7 country with higher emissions today than in 2015) is “actually negated or reversed due to import of embodied emissions.” The report proposes a handful of policy tools that could help and calls, fundamentally, for a shift to using consumption-based emissions for climate agreements, disclosures, and tracking.

Unless consumption-based accounting is used, countries may meet their Paris Agreement targets while being responsible for increasing emissions abroad, as occurred with the Kyoto Protocol.

Close the carbon loophole (10 minutes)

One Earth, 2021

This is a collection of responses to the question, “Where are the opportunities to close the carbon loophole and facilitate sustainable and fair trade?” The selected contributors share an ideological tilt that differs from what’s typical in this newsletter, but I find it an informative look at how many “climate wonks” and economists see this problem. First, they’re almost unanimous in understanding the “carbon loophole” as driven by increasing regulation of carbon emissions in northern countries. I agree that’s a plausible mechanism – and is one that may in fact cause an uptick in imported emissions over the coming years as we see increasing regulation of carbon in the north – but the growth of carbon outsourcing correlates more closely, in my view, with globalization generally. The carbon-specific piece of it was largely incidental to the relocation of production to places with cheaper labor and otherwise lower costs. Because of their interpretation of the cause, these academics mostly see some kind of carbon tariff or “border adjustment” as the solution – something that levels the playing field across different regulatory regimes. In the absence of some kind of binding international agreement regulating carbon, there is a strong case to be made for a border adjustment, but as some contributors noted, it’s important that these policies be coupled with (often promised but rarely delivered) transfer payments to the global south to allow them to decarbonize more quickly without devastating their economies and people. It’s also worth noting that there is a degree of irony in the fact that many of these respondents (and others) are worried that proposed carbon tariffs would violate the international trade regime enforced by the US/WTO while simultaneously failing to recognize the role that very regime has played in creating the problem it is now blocking resolution of.

Carbon colonialism must be challenged if we want to make climate progress (5 minutes)

Laurie Parsons, The Conversation

This piece looks more closely at the UK. The UK’s sixth carbon budget – they’ve never missed one of these targets! – was announced in April last year and established a goal of reducing emissions by 78% from 1990 levels. In these terms, the UK is far closer to the scale and timeline of emissions cuts that the north needs to achieve than any other country. But as Parsons writes here, the UK takes advantage of methodological nationalism to allow itself to claim victory while really just outsourcing its emissions to the global south. Parsons also raises some questions about consumption accounting altogether: global supply chains are “inherently murky.” The report cited earlier in this newsletter uses “multiregional input-output” modelling to estimate the implicit trade of emissions; supply chains are not just complicated, but complex, to the point where we do not and likely cannot have a deterministic understanding of them at the scale required to be accurate. The rise of south-south emissions trading has the potential to make this even more “murky.” Money laundering works, in principle, by moving money around enough times that it becomes impossible to trace its origin. Tor – a technology used for anonymous web browsing – works exactly the same way. It’s not hard to imagine carbon emissions disappearing in a similar fashion. Even if we implement border tariffs or pass more clean procurement legislation like California’s Buy Clean Act, we may still be heading down the path towards a world that is “net zero” but hasn’t actually reduced emissions at all.

Like what you’re reading here?

Sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue and consider forwarding this email to a friend or colleague.