Sacred Headwaters #2: Planetary Boundaries and Doughnut Economics

An introduction to the planetary boundaries framework and the complex systems involved in earth's capacity to sustain human civilization.

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you missed the first issue, please check it out here. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time.

Sacred Headwaters #2: Planetary Boundaries and Doughnut Economics

In this newsletter, we’ll learn about some of the problems facing humanity beyond the climate crisis and explore how we can frame the challenges of sustaining human civilization within the earth’s inherent limits. The earth system is full of complex non-linear network dynamics which makes separating concerns difficult -- climate change impacts biodiversity, impacts freshwater availability, etc. -- but it’s important to recognize that the human status quo is threatening -- and as a result threatened by -- a number of different pillars of the global ecosystem that are critical to earth’s ability to support us.

How Defining Planetary Boundaries Can Transform Our Approach to Growth (20 minutes)

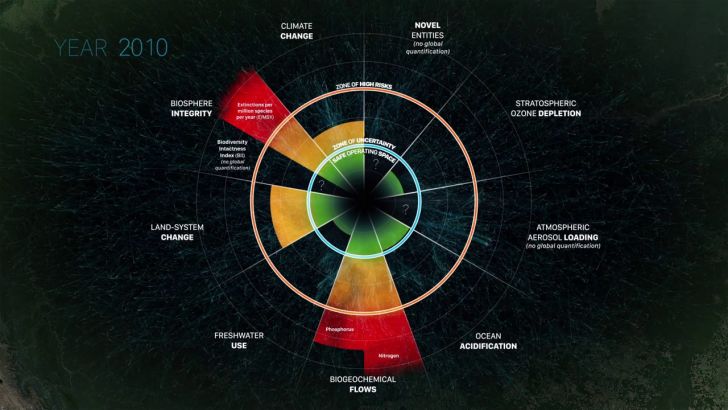

This article introduces the planetary boundaries framework, a way of thinking about the different, interacting conditions of our planet that must be maintained for advanced life to continue to exist. Human civilization has thrived over the last 12,000 years of stable climate and ecosystem; what will happen to humanity if we lose that stability is unknown, but it will certainly lead to fundamental alterations in, if not destruction of, the way we live. The authors have identified nine separate (but interrelated) global limits and attempted to define thresholds at which boundaries are overshot, potentially triggering major transformations in the earth system.

This visualization provides a quick timeline of which boundaries we’ve exceeded and when:

There are a few important points made by this framework. First, while climate is critically important to human success, it is not the only boundary we are exceeding. Even if we were to “solve” the climate crisis (so to speak), our work towards sustainability would be far from over. Second, and perhaps more uniquely, the idea that there are fundamental -- and finite -- limitations on human activity forces a new perspective on our civilization’s premise of indefinite growth, raising the question, if we can’t grow indefinitely, how can we continue to prosper?

(Note -- for further reading on planetary boundaries, explore the resources on the Stockholm Resilience Center website).

Doughnut Economics (10 minutes)

Economist Kate Raworth expanded the planetary boundaries framework to answer that question. She introduced the concept of an inner circle in the planetary boundaries diagram, one that represents meeting the minimum needs of the people of earth -- something we are not doing on a global scale at this point, despite years of unprecedented “growth” in the global economy.

The finite nature of the planetary boundaries and the failure of economic growth to bring the majority of the planet’s human population up to acceptable living standards brings the very notion of economic growth -- as we’ve understood it thus far -- into question. Raworth proposes redefining our measures of success to more accurately track real metrics like -- are we within our planetary boundaries? And, are we meeting the needs of earth’s population? There’s a great interactive diagram showing the annotated “doughnut” on her website. Raworth and Johann Rockstrom participated in a podcast hosted by the Guardian that outlines planetary boundaries and doughnut economics and discusses the practical implications and applications of those concepts. It’s worth a listen for some clearer explanations and context (25 minutes).

The Whale Pump (10 minutes)

I’m including this article because it shows how a specific feedback system impacts multiple planetary boundaries. To sum it up in a sentence, the lifecycles (and migrations) of whales and the phytoplankton they feed on are a massive carbon sink; a single great whale can sequester 33 tonnes of CO2. There are innumerable systems like this in the earth system and the complexity is almost unimaginable, but what they make clear is that all our planetary boundaries are interrelated: if you reduce biodiversity, you impact climate. If you acidify the ocean, you impact biodiversity -- which in turn impacts climate, which continues to reduce biodiversity. And so on. Every boundary is intertwined, and throughout the Holocene, those boundaries have been maintained at stable levels through natural feedback loops in the earth system. We -- humans -- are pushing those feedback loops over thresholds and are at imminent risk of destabilizing the equilibrium that has allowed human civilization to thrive.

Book Recommendation: Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth

If you’re like me -- educated in a WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) country in the last few decades -- you were likely taught the ideas of neoliberal economics at an early age and as fact, believing that economics is a hard science of market dynamics that fundamentally defines the value of everything in our culture. Personally, I went so far as emailing Greg Mankiw, author of Principles of Economics and economics professor at Harvard, for life advice while applying to college. In Doughnut Economics, Raworth traces the evolution of neoliberal economics from its beginnings in political economy theory, pointing out its fundamental flaws along the way and mapping out its pervasive impacts on culture and thought processes. She emphasizes the things it fails to account for and why it fails -- including, but not limited to, long-term damage to the environment. More importantly, she begins to look at how we can reshape our understanding of economics to be goal-driven, asking, how can we get into and stay within the “safe and just operating space for humanity” -- or, how can we change the structure of our economies to sustain life inside the doughnut? It’s both a theoretical and practical look at reshaping the world economy towards sustainability that draws on a fascinating variety of behavioural economics studies and real-world examples, and it’s a fairly quick and enjoyable read.