Sacred Headwaters #53: Radical Municipalism

Electoralism can often feel like a dead-end for the kind of radical transformation needed to avert ecological catastrophe. Can we build power locally as a strategy for global change?

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity, about the power structures blocking change, and about how we can overcome them and build a future in which all of humanity can thrive. If you’re just joining, consider checking out the first issue for some context and head over to our table of contents to browse the whole library. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but they do build on concepts over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Table of Contents

Sacred Headwaters has a table of contents intended to allow readers to “catch up” more effectively, facilitate using Sacred Headwaters as a reference, and give a better picture of what the newsletter is about for those who are just joining.

Issue #53: Radical Municipalism

This issue is a theoretical underpinning for many of the issues in the (still ongoing) “TINA” — “there is no alternative” — series. I’m separating it from the series (by title, at least) to keep the series itself focused on actual, reified approaches to the construction of alternative systems. There will be more TINA issues in the future (among other radical projects, I’m interested in looking at Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi and Barcelona en Comú), but wanted to take a look at one of the theories of change underpinning, sometimes explicitly, sometimes not, these approaches.

Perhaps the most fundamental question that anti-capitalists of all stripes wrestle with is how exactly do we overcome capitalism when it’s become so effective at its own reproduction, and when it retains such a firm grip on existing power structures around the world?

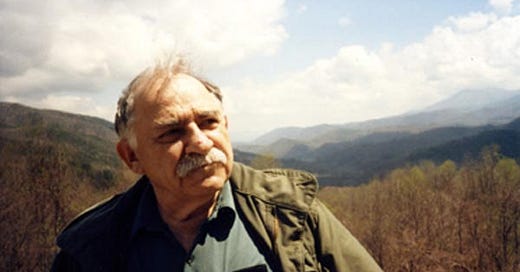

Radical municipalism is one answer to that question, developed as a theory most prominently by the American social ecologist Murray Bookchin (though he typically referred to it as “libertarian municipalism”). Adherents argue that there are two primary reasons that attempting revolution at larger scales fails: first, that capitalism is too entwined with modern institutions and is as a result, more or less impervious to our efforts, and second, that the state itself is part of the problem — even a socialist vanguard successfully seizing state power would not create the world we need.

Bookchin argued that the only way to challenge the grip capitalism has on society — and, relatedly, the only way to avert ecological crisis — is to build power at a local level through radical participatory democracy and the construction of explicitly oppositional alternative systems. This doesn’t necessarily imply participation in local electoralism through existing structures, but Bookchin and other proponents often do advocate that strategy as it’s often the easiest path to power.

How this local power development then leads to ending capitalism at a national or global scale is, of course, the most interesting piece of the puzzle, and it’s what clarifies that initiatives like the Transition Movement are not radical municipalist movements, while more openly oppositional ones like the movement in Rojava might be. (It’s worth mentioning here that Abdullah Öcalan, one of the leading theorists behind the Rojava movement, has said that he is heavily influenced by Bookchin’s work). Radical municipalism relies on the idea of “dual power” to answer this question — building local, radically democratic nexuses of power that, as they grow, become increasingly incompatible with capitalist state power. Radical municipalism aims to take steps in the short-term that alleviate the escalating harms of capitalism, and in so doing build an alternative power that eventually, by replacing it and exposing its contradictions, leads to the collapse of the state.

This intent is what differentiates radical municipalism from isolated efforts at mitigating the harms of or withdrawing from capitalism — cooperatives, community gardens, and even broader movements like Transition. As we’ll read below, Bookchin has some disparaging things to say about those efforts which he names as “communitarianism.” I’m not sure I agree completely — one hopes that these efforts contribute in some way at least to the broader mission of reminding people that yes, there is an alternative — though some of what he writes about cooperatives specifically certainly resonates.

In this issue, we’ll read more about what radical municipalism is and the role that municipalist strategies can play in helping bring about the transformation of society we need (for so very many reasons).

I should note that Bookchin was in many ways a prickly character, and the term “libertarian” that he uses often comes today with many right-wing capitalist connotations. Don’t write off the ideas of radical municipalism just for those reasons, as it’s an ideology that is driving, or at least descriptive of, many of today’s most inspiring movements.

Radical Municipalism: The Future We Deserve (10 minutes)

Debbie Bookchin, ROAR Magazine, 2017

In this piece, Debbie Bookchin, Murray’s daughter, attempts to summarize what radical municipalism is, how her father arrived at municipalism as a solution to the stagnation of the left in the latter half of the 20th century, and how municipalism might help us build a utopian, non-capitalist future. She argues that her father's political theory developed as a response to two things: first, his feeling that traditional Marxist thought did not truly prioritize or create the conditions for freedom, or what she calls his "search for a more expansive notion of freedom," and second, his realization that the ecological catastrophes of his formative years (and those we continue to endure today) were, at their core, social in nature: an inevitable result of the way we organize our relations with each other and with the non-human world (i.e. capitalism). Debbie situates her father's municipalism as a solution to the current "lesser of two evils" dilemma of modern democracy, arguing (and it doesn't take too much arguing, these days) that "we will never achieve the kind of fundamental social change we so desperately need simply by going to the ballot box."

While the piece doesn’t go into great detail in terms of the nuts and bolts of municipalism, it’s worth highlighting the section where she references super-municipal structures: while radical municipalism is, ultimately, about abolishing the state, its stateless future still has regional and even global coordination via confederation between more directly democratic and local organizations.

Thoughts on Libertarian Municipalism (25 minutes)

Murray Bookchin, Left Green Perspectives, 2000

In this essay (originally given as a speech), Bookchin gives a wide-ranging overview of his conceptualization of libertarian municipalism, potential pitfalls, and how it can be a tool for change. As mentioned in the introduction, he spends quite a bit of time in this piece critiquing what he calls “communitarianism” precisely because he sees people mistakenly lumping radical municipalism in with things like cooperatives, ecovillages, community gardens, and so on. While there are shared characteristics — communitarianism is undoubtedly about building alternative systems to the dominant globalized capitalism — radical municipalism is explicitly and deliberately oppositional and maintains a clear goal of building power in such a way that, eventually, the state itself will fail.

Further down the piece, Bookchin explains the libertarian municipalist idea of “dual power” and how it differs from certain historical uses of the phrase, emphasizing that for municipalists, it is a "means to a revolutionary end" — the end being a stateless society of federated municipalities.

I found the section titled “Education for Citizenship” interesting. While I think there are aspects of it that are undoubtedly correct — vibrant direct democracy requires a citizenry that is actively engaged, and education is no doubt important to that — his heavy emphasis on ancient Greek and Enlightenment ideals is a bit hard for me to swallow. I’m not sure that most radical municipalists today are on the same page as him in this area. Drawing from Greek thinkers, Bookchin argues that enlightened citizenship isn't an inherent quality that's been beaten out of us by capitalism, it's something that must be taught and learned. In her piece above, Debbie actually hinted at something that I think runs counter to this: the idea that radical democracy as a practice can itself transform the people practicing it, encouraging them to become active citizens just by empowering them. As she puts it, “in the very act of doing politics we become new human beings.” The readings in the issue on Rojava make a similar argument.

The promise of radical municipalism today (10 minutes)

Symbiosis Research Collective, The Ecologist, 2018

Bookchin developed his idea of municipalism throughout the latter half of the 20th century, arguing that it was a good fit (or the only fit) for the conditions of the time. The authors of this piece argue that today, radical municipalism is more relevant than ever because of a combination of global processes that have transformed work, the workplace, and capitalist accumulation, making traditional avenues of left-wing organizing all the more difficult. And it’s not just theoretical: they argue that municipalism is indeed seeing a global surge, although they are liberal about including what Bookchin would have called “communitarian” efforts. The authors suggest that municipalism isn’t on the rise just because it’s the most strategic response to our political moment, but also because it’s a natural one, a counter-reaction to the atomization and alienation produced by globalized capitalism.

How radical municipalism can go beyond the local (15 minutes)

Symbiosis Research Collective, The Ecologist, 2018

In this follow-up piece, the Symbiosis Research Collective responds to a number of common criticisms of radical municipalism as an approach to the related goals of overcoming capitalism and addressing the ongoing ecological crisis (what Bookchin considered the ultimate contradiction of capitalism). The first criticism that the authors address is one that’s worth highlighting specifically because it comes up in so many different contexts: “because of climate change, we don’t have time.” The authors’ response is specifically municipalist, but it’s similar to the response I would give in other contexts as well: if you see climate change as just one facet of a broader ecological crisis, and you see the ecological crisis in turn as a symptom of capitalism’s insistence on perpetual growth and consumption, there is no faster way to resolve it than by ending that insistence. For the authors, that means that — given their argument that municipalism is the best anti-capitalist strategy we have — the best way we can act with the urgency the climate crisis demands is to pursue municipalist strategies. They also point out that many municipalist strategies are synergistic with climate justice, evidenced by the plethora of (admittedly mostly liberal) city-led initiatives leading the way on climate action.

The piece also addresses how local action can have global impacts, particularly under the globalized and financialized form of capitalism we see today, and how radical municipalism, while focused on a long-term revolutionary end, can deliver incremental non-reformist reforms along the way.

Book Recommendation: Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052-2072, M. E. O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi

This book is fascinating and one of the first books of its kind: it’s a snapshot of a utopian near-future, telling the story of climate collapse, international revolution, and communalist (or radical municipalist) recovery. I think Ministry for the Future is the only other book I’ve read that attempts something similar, though it depicts a fundamentally different outcome. The future this book outlines is messy (or perhaps, realistic) — it doesn’t shy away from the violence the world may see as state power declines, reactionary right-wing forces (closely tied with existing police and military) gain strength and boldness, and communities are forced to fight for their survival — but what is born on the other side is a pluriversal anarchist utopia. The story is told as a series of interviews of a diverse set of people and covers a variety of topics including perspectives on how the revolution (not really singular) unfolded, and descriptions of how life operates in a number of different communes in the greater New York area, and a window into how a radically democratic post-capitalist society is attempting to coordinate ecological restoration on a global scale. It’s a fairly quick read and I highly recommend it!

If you’re interested in some of my other writing, I just published an investigative report into Canada’s “carbon bombs,” 12 massive fossil fuel projects that are pending or underway, with Ricochet Media. There’s also a great visual component by Elysse Deveaux to go with it.

Like what you’re reading here?

Sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue and consider forwarding this email to a friend or colleague.

Explanation of horizontal governance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wywMhg604W8

Hi Nick, I've learned a lot from you and wanted to thank you for your passion, insights, and grounded optimism. When I read about Radical Municipalism, the first thing that came to mind was the growing "constitutional sheriff" movement in the U.S. Living in a county with a "constitutional sheriff", this isn't the direction I would hope that Radical Municipalism would take. Nonetheless, I wonder if there are similar yet much more positive community-centric examples that are gaining a similar level of traction. Best wishes from Freetown, Brian