Sacred Headwaters #47: TINA Pt 1 - Building Alternative Systems – Transition Towns

Transition Towns, a framework for building climate resilience through an emphasis on localization, has been incredibly successful. But is it fundamentally reformist or radical? Can it be both?

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and head over to our table of contents to browse the whole library. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Table of Contents

Sacred Headwaters has a rudimentary table of contents intended to allow readers to “catch up” more effectively, facilitate using Sacred Headwaters as a reference, and give a better picture of what the newsletter is about for those who are just joining.

Issue #47: TINA Pt 1 - Building Alternative Systems – Transition Towns

This issue became part of a series after publication:

Issue #47: TINA Pt 1 - Building Alternative Systems – Transition Towns (Feb 28th, 2022)

Issue #48: TINA Pt 2 – Catalan Integral Collective (Mar 13th, 2022)

The last few issues – and much of this newsletter to date – have focused predominantly on identifying and exposing the power structures that are driving the climate and ecological crises and the vastly unjust nature of the world today. But exposing and even challenging these power structures can only get us so far: if we’re not building durable, alternative systems at the same time as we struggle against the forces driving ecological collapse, we risk failure and we risk the potential of seeing the current system replaced with something even worse. It’s not hard to argue that we are careening down that path as I write this: the far right is on the rise globally, military tensions between nuclear powers are high, and rising energy and food costs (in part due to escalating climate and ecological catastrophe) are having devastating and further destabilizing impacts.

Part of the need for social movements to work on alternative systems is straightforward: to prove that a better world is possible in the face of an environment of cultural production that insists what we have is the pinnacle of “human evolution” (whatever that means). Green New Deal politics have embraced that challenge, but they’re less about replacing the system and more about envisioning a version of what we have today that’s less terrible. Things like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s “Message From the Future” and Eric Holthaus’s The Future Earth attempt to paint a hopeful picture of the future that empowers people to take action today. But these stories, and Green New Deal politics more generally (what’s often called “green Keynesianism”), are rooted in the idea that we can win power without fundamentally changing the political structures that govern global society. That we can address the climate crisis within the bounds of what we call “liberal democracy,” a system that has been closely tied throughout its entire history to systematic racialized oppression and dispossession, the massive growth of wealth inequality, and of course, climate and ecological collapse.

I’m not trying to argue here that attempting to organize to win power within the existing structures of nation-states is wrong. It’s definitely not! But I think it’s important that we ask the question – particularly as the climate crisis deepens and the wealthy world continues its obstinate stand against action of any kind – what if so-called liberal democracy, or perhaps the very idea of the world as a group of nation states, is incapable of reversing the course of capitalist-driven ecological collapse? Or at the very least, is incapable of doing it on the kind of timeline necessary to prevent its own climate impact-driven implosion?

This is where the idea of building alternative systems – concurrently, of course, with fighting to disrupt power – becomes more than just filling in gaps in the status quo or creating capacity for hope. It is about building alternative paths to climate justice. It’s about building (or rebuilding) the capacity for mutual aid and resilience. Life on this planet is getting worse for billions of people and that’s likely to continue for at least a couple decades, if not longer. We can either work to cultivate systems that mitigate that suffering and prepare for a more difficult world or we can bury our heads in the sand, and it’s pretty clear that global north governments are in the latter camp. In climate-specific terms, building alternative systems can help us work towards both mitigation and adaptation, reducing our dependence on fossil fuels at a variety of scales by reducing our dependence on capitalist economic growth, and simultaneously, building redundancy and support networks that will mitigate the suffering caused by the damages of climate change.

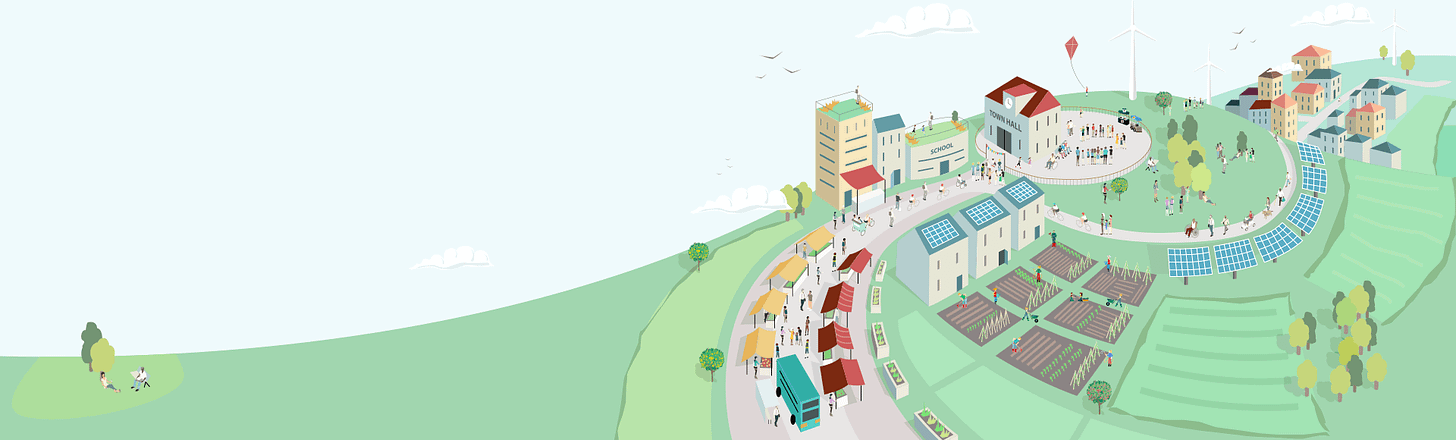

Over the next few issues, we’re going to read about a variety of different approaches to this idea from both practical and conceptual standpoints. This first issue focuses on the Transition Towns initiative, a movement to relocalize economies and energy production at small scales founded in the UK in 2006. Transition is probably the least “radical” – by design – of the movements we’re going to read about, but its proponents would argue that its deliberate palatability has enabled it to grow rapidly and created a remarkable decentralized network of empowered communities. It’s also the kind of thing that, if you find yourself reading this newsletter and wondering, “what the hell can I do?,” you can very easily get involved in! The reading in this issue begins with a piece about the need for alternative systems, then moves on to what Transition Towns are, how the model works, and what some of its issues or shortcomings are.

Sustainable development is failing but there are alternatives to capitalism (5 minutes)

Ashish Kothari, Alberto Acosta, and Federico Demaria. The Guardian, 2015.

In this 2015 op-ed, the authors make the case that not only has international climate policy failed, but the entire framework of sustainable development from the Brundtland report (1987) on has failed – or been a farce. Sitting here nearly seven years later, after COP26, it’s hard to make any other assessment. The problem, they argue, lies in the de facto insistence on green capitalism as the path to climate and environmental protection and the deliberate obfuscation of the underlying structural causes of the problems we face today. In answer to this, they write, “critique is not enough: we need our own narratives,” and offer a sweeping overview of inspiring and transformative approaches to being cropping up today. Their list includes Transition Towns and degrowth (which I think often masquerades as less radically transformative than it really is), a variety of movements in the global south like buen vivir, and anti-colonial, anti-capitalist movements like the Zapatista and the autonomous Kurdish territories in Rojava. The next few issues will focus on these different movements and what we can learn from them.

Transition Towns – the quiet, networked revolution (10 minutes)

Rapid Transition Alliance, 2019.

This article is a timeline and overview of the Transition Towns movement and the associated Transition Network. It speaks to how rapidly the transition movement has spread and how diverse and decentralized it is, with different Transition initiatives having worked on things ranging from community-owned renewable energy production to local currencies to community land trusts and affordable housing. Transition’s “hub” model is an interesting way of seeding locally-led movements that’s proven wildly successful – there were 34 hubs when this article was written and there are over 1000 “transition groups” registered with the network today. This article does raise some questions, pointing out that local change is often constrained by higher level political decision-making and the economic system more broadly and asks whether Transition can really serve to simultaneously make local changes and build capacity to win structural change. I share these concerns, though I do think there’s something revolutionary even about something as small as a community garden: the very act of sharing public space to produce food is a challenge to the dominant economic paradigm of ownership and commodification.

“The Rocky Road to a Real Transition”: A Review. (15 minutes)

Rob Hopkins, 2008. This is a response to a critique of the transition towns movement written by Paul Chatterton and Alice Cutler.

Rob Hopkins, the founder of the Transition Towns movement, wrote this piece defending Transition from a left-wing critique early in the movement’s life. According to Hopkins’ characterization, the critique makes these arguments: first, that Transition obscures the underlying structures and power dynamics of global capitalism and in so doing, prevents us from challenging them; and second, that Transition’s desire to work with existing power structures – particularly, with municipal governments – makes it and its message prone to cooptation. Hopkins believes that these critiques are actually Transition’s strengths, and there’s obvious truth to the argument that its apolitical nature has helped it grow and appeal to a range of people. But his defense of its theory of change depends largely on the movement’s original premise: that the world was, in 2006-2008, experiencing “peak oil,” meaning that communities would be forced by market conditions to draw down their energy use because of a dwindling oil supply. That has unfortunately proven false (thanks Obama!) over the last 15 years. The climate crisis itself is reason enough to continue pursuing Transition (and the movement is clear on this), but the idea that oil supply conditions would force rapid change whether politicians were ready for it or not just hasn’t played out. In particular, Hopkins suggests that the idea that there are “[people] in positions of power who will cling to business as usual for as long as possible” is absurd, and unfortunately, it becomes clearer every day just real those forces are. As such, I think many of the critiques of Transition that the original authors levied remain strong – can a movement that encourages disengagement and withdrawal actually transform society? Hopkins’ strongest point is that he sees Transition as a just one strategy among many – that others can (and perhaps should) concurrently pursue more confrontational efforts to transform the political world. To his credit, I have no doubt that his thinking on these issues has evolved over the last 14 years as the movement has developed; some of his more recent work can be found on his website.

The Transition Movement: Questions of Diversity, Power, and Affluence (40 minutes)

Esther Alloun and Samuel Alexander, The Simplicity Institute, 2014.

This paper expands on some of the critiques Hopkins responded to in the earlier piece from a different circumstance in both time and positionality: it was written six years later, when the movement was much further developed, by two authors who themselves participate in a local Transition initiative. It includes a detailed overview of Transition’s model and approach to change before diving into a variety of critiques focused on Transition’s diversity of appeal (specifically, its lack thereof) and on whether or not its apolitical nature ultimately renders it incapable of driving the political change that it seeks. The authors are harsh but fair, and ultimately seem to conclude that Transition has the potential to become a radical (as opposed to reformist) movement if it chooses to focus more on the political and more on questions of who is included – and excluded – by processes of localization and resilience-building. They raise a series of questions that cut incisively to the core of the issue:

if the movement grows enough food itself and sets up farmers markets and community gardens, can it eventually undermine industrial agriculture? If the movement develops alternative currencies, can it undermine global finance? If it creates more cooperative business ventures, can it undermine corporate capitalism? If it creates more decentralized, small, local-scale renewable energy projects, can it make coal companies irrelevant and change energy planning and policy? Is localisation of production and consumption the best way to achieve a more sustainable and equitable future? Or, on the other hand, does the movement need to take state power, or more directly challenge state power...?

Having used the term “resilience” myself in the introduction to this newsletter, it’s worth noting something the authors point out in section 5.1: “resilience” has, in many ways, replaced “sustainability” as the 21st century climate buzzword. The New York Times even ran a piece in 2012 titled “Forget sustainability, it’s about resilience!” This sort of cooptation happens so fast that there’s no point term policing (we’d have to constantly come up with new terms), but it’s important to be conscious of. As we’ve seen in real time over the last two years (“build back better” and “just transition” are two prominent examples), the neoliberal political and media machine can co-opt movement rhetoric almost instantly, and without vigilance, it can be extremely disempowering.

How to Get Involved

This issue has been critical of the Transition movement, but I should be clear that while I think Transition has flaws, it remains an incredibly effective toolkit for small-scale community organizing and many of the projects Transition initiatives work on (affordable housing, community energy, food security) are incredibly important, even if they, in isolation, cannot achieve the scale of change needed. So, with all that said, I’d encourage anyone who is inspired by this kind of stuff and feels that there may be an opportunity for Transition or Transition-like organizing in their community to browse the Transition Network’s resources. They have a very helpful guide that is really an instruction manual for action-focused community organizing.

Like what you’re reading here?

Sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue and consider forwarding this email to a friend or colleague.