Sacred Headwaters #7: Degrowth

Some economists believe it's time for a new paradigm to govern global progress -- and that our existing one is fundamentally incompatible with sustainability.

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and read through the other issues when you can. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Sacred Headwaters #7: Degrowth

The economist Simon Kuznets is credited with coming up with the concept of GDP as a way to measure the impacts of the Great Depression and the progress of FDR’s efforts to improve the economy. At the time, Kuznets expressed a variety of concerns about the metric and many continue to criticize its value as a metric (even the Economist). I’d go so far as to say that there’s a degree of agreement about the shortcomings of GDP, but despite that, the goal that it’s used to measure — constant growth — is almost never questioned at a policy level. A group of economists are trying to change that, arguing that economic growth — continued, indefinite growth of national income or production, however you measure it — is fundamentally incompatible with a sustainable civilization.

In this issue, we’re going to look at degrowth — why some economists believe growth is unsustainable, whether or not growth actually correlates with prosperity, and how we might be able to prosper without growth. This issue is an introduction to the concept and we will explore more detailed work on pathways to degrowth in future issues. If you haven’t read issue #2, “Planetary Boundaries and Doughnut Economics,” I’d encourage you to read that first. Kate Raworth’s “doughnut economics” framework falls within the degrowth umbrella (although she’s not fond of the name “degrowth”).

Raworth makes this eloquent summation:

We have an economy that needs to grow, whether or not it makes us thrive.

We need an economy that makes us thrive, whether or not it grows.

“Why Growth Can’t Be Green” (10 minutes)

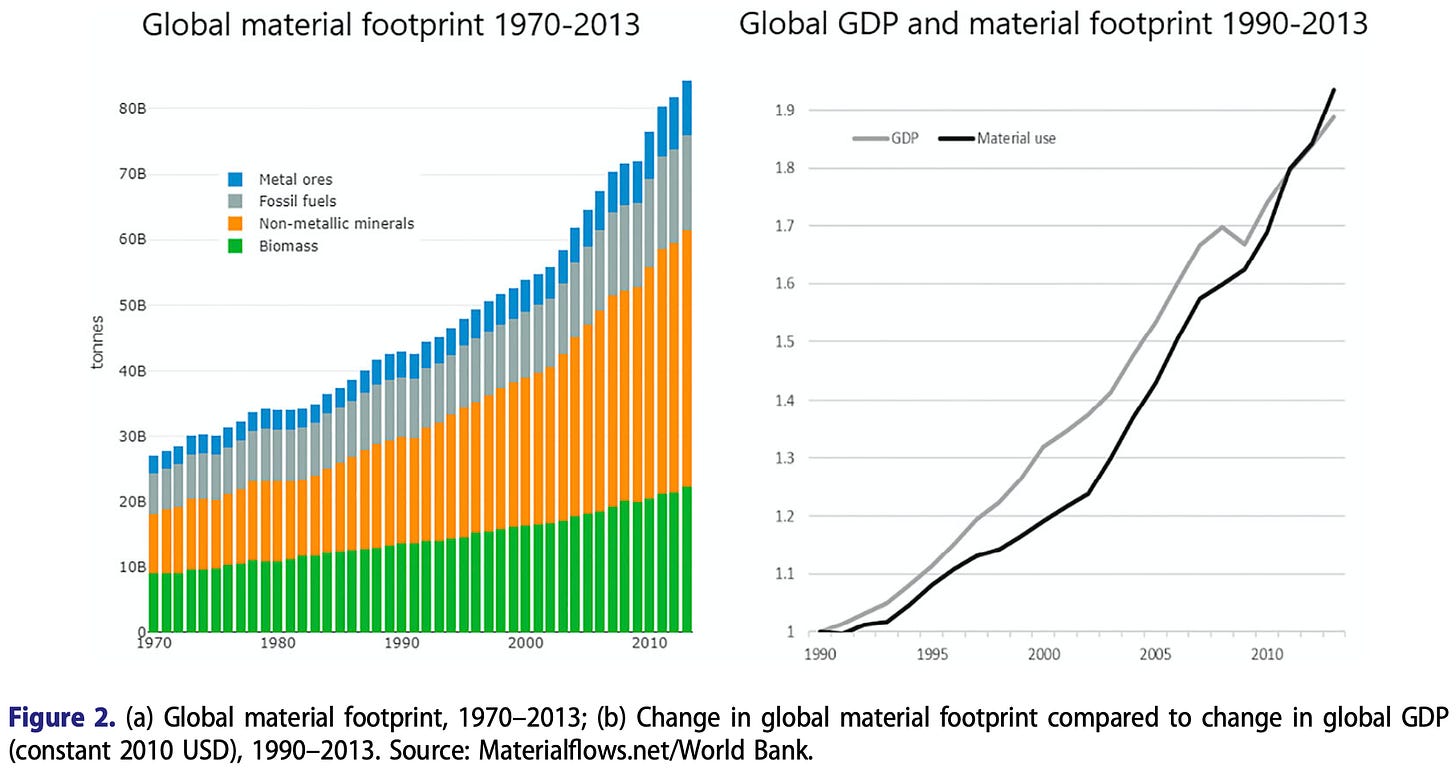

The UN has been talking about sustainable development since 1987 but, more recently, in the face of rapidly accelerating biophysical crises, they coined the term “green growth.” The idea is to achieve growth — GDP growth — that is “absolutely decoupled” from natural resource use and — most immediately — from greenhouse gas emission. In other words, “green growth” is GDP growth that happens concurrently with a reduction in total resource use. It’s based on the understanding that perpetual growth in resource extraction is fundamentally impossible, and that historically, global growth has been tethered tightly to global resource use.

In this piece, Hickel argues that “green growth” is impossible — that GDP cannot be absolutely decoupled from natural resource consumption. He cites a number of studies (see his paper linked below for citations) that found, even with very optimistic assumptions about global environmental policy, that resource use will continue to grow as long as global GDP continues to grow. Hickel doesn’t spend much time on alternatives, but the ideas he throws around in the last few paragraphs are some examples of potential paradigm shifts in culture and governance that could enable a human civilization to thrive without growing.

Note: this figure is from a more rigorous but similar piece that Hickel published in the journal New Political Economy available here or directly as a PDF here.

“Unraveling the claims for (and against) green growth” (10 minutes)

I mentioned “absolute decoupling” above. “Relative decoupling” is another important phrase that means the rate of natural resource use growth is smaller than the rate of economic growth (GDP), but still positive. It represents increases in efficiency, but not a separation of growth from resource use.

In this article, the authors look at arguments on both sides of the “green growth” debate, pointing to real-world examples of relative decoupling and analyzing the possibility of absolute decoupling. Their literature review reaches two conclusions. First, there is no convincing evidence that absolute decoupling is possible on a global scale. Second, even if absolute decoupling is possible (through technical innovations, solar energy use, whatever else), it would need to be achieved on an incredibly short timescale in order to avoid the catastrophic climate impacts forecast by the IPCC, something that’s almost certainly impossible given the lack of progress thus far.

The authors leave off with this powerful note that distinguishes the decoupling of “well-being” from the decoupling of growth:

Decoupling well-being from material throughput is vital if societies are to deliver a more sustainable prosperity—for people and for the planet.

“At this rate, it will take 200 years to end global poverty” (10 minutes)

A common retort to ending GDP growth is that we need economic growth in order to fight (or end) poverty globally. It’s the unspoken “good” of pursuing economic growth at all costs, eloquently spoken out loud by Ronald Reagan: “a rising tide lifts all boats.” Unfortunately, the reality doesn’t hold true. In this article, Hickel points out that GDP gains over the last thirty years have almost entirely excluded the global poor. Given the relationship between income growth in poor countries and global GDP, it would take 200 years of steady growth to end global poverty — which, aside from just being an obvious good, is the number one Sustainable Development Goal.

This analysis doesn’t tell us what the path to ending poverty looks like. But it does tell us that pursuing endless economic growth is not a path to ending poverty, nor is growth a precondition of ending poverty. The idea that global economic growth will be the driver that ends poverty seems especially problematic in the context of climate change and the need to limit carbon emissions.

For more detailed analysis that reaches similar conclusions to Hickel, check out “Incrementum ad Absurdum: Global Growth, Inequality and Poverty Eradication in a Carbon-Constrained World” from the World Economic Review.

“Yes, We Can Prosper Without Growth: 10 Policy Proposals for the New Left” (15 minutes)

It’s easy to say, “Indefinite growth is incompatible with sustainability.” It’s much harder to imagine alternatives to an ideology so ubiquitous and self-perpetuating that most of us don’t even realize it’s an ideology. In this article, Giorgos Kallis lays out ten concrete policy proposals consistent with degrowth and with transitioning to a world where we thrive — but don’t grow. Some of these will seem radical while others may seem obvious. Ending fossil fuel subsidies is a no-brainer — although it remains frustratingly elusive. Universal basic income (UBI) was a radical idea in the USA — despite support among traditional neoliberal economists — until this year when Andrew Yang introduced it to the national dialogue. Cap and trade programs already exist for CO2 emissions, though they need to be strengthened, applied globally, and extended beyond greenhouse gases. Kallis’s degrowth policy proposals are an integration of social justice reform, environmental reform, and optimization; he believes that together, these policies (and others like them) can increase prosperity while limiting growth — in other words, can achieve sustainability.

Podcast: “The Neoliberal Optimism Industry,” Citations Needed

I’ve had quite a few readers ask me about podcast recommendations. I’ve included a couple buried in text links in other issues, but I’m trying something new in this issue and including a podcast as a headline item. In this episode, Citations Needed looks at the pervasive narrative that growth is making the world a better place. The authors take a hard look at this claim, assessing the metrics that are used to make it — and the motivations of those who are making it. It includes an interview with Jason Hickel, a prominent degrowth thinker, self-described “economic anthropologist,” and author of two (!) of the pieces earlier in this issue.

Book Recommendation: Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era, Giacomo D’Alisa, Federico Demaria, and Giorgos Kallis (eds)

Note: the official website of the book is linked above. It’s available as a free PDF download here.

The concepts of growth and development are so deeply embedded in our consciousness as goals that it is difficult to question them and propose alternatives. Degrowth is an alternative paradigm and this book — a collection of essays from a range of authors — aims to define a set of concepts with which we can begin to think outside the constraints of traditional neoliberal global economics. The book attempts to define (or in some cases re-define) and contextualize concepts including “peak oil,” GDP, and the commons, bringing them into a conversation with concepts like conviviality, happiness, and care. Part 3 focuses more on practical transitional terms — basic and maximum income, co-operatives, work sharing, and more. Ultimately, it provides a broad overview of the landscape of degrowth thinking: how can it replace growth as an ideology? How can we continue to thrive without growth? And, what does a degrowth world look like?

I haven’t read it yet, but I’m looking forward to it.

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe if you haven’t already and share if you have:

Nick, I didn’t read all of the linked articles, but am really glad to see you address the issue of growth. My other favorite quote (along with Ken Boulding’s that is included in one of the readings) is by Edward Abby:

“Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.”

I also wanted to mention the book by Paul Gilding, The Great Disruption, which makes the case that we will at some point have to make the difficult transition from a growth economy to a steady-state economy and that the transition will be very difficult. Gilding also gave a TED talk that you can find online.

Keep up the good work,

-Alex Wilson