Sacred Headwaters #11: Circular Economy

Waste is a product of all life. But in natural systems, it's always recycled. Can our human systems be restructured to operate the same way?

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and read through the other issues when you can. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Issue #11: Circular Economy

Waste is an inherent part of life. Closed systems — cells, organisms, etc. — take in resources from their environment and excrete metabolic waste back out. On earth, those waste products are then used by and cycled through a series of other organisms. The kindergarten example is the high-level explanation of the carbon cycle: animal respiration emits CO2 into the atmosphere, plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, animals eat plants, and the cycle continues. The reality, of course, is that earth’s atmospheric composition is governed by a far more complex system that we don’t completely understand, but for our purposes today, the important piece is that waste emitted by one organism is consumed by another, cycling through a sequence that leaves no resource “discarded.”

In our human world, things are almost unfathomably different. First, consider it from a value perspective. If you buy a product, the expectation is that you’ll discard the packaging. That packaging cost money to produce. Say the packaging for your new computer cost a dollar to produce. By discarding that packaging, you’re removing that dollar from circulation. …It’s a crime to destroy paper representations of money in the United States.

Perhaps more importantly, when you discard that packaging, natural resources are being removed from circulation, whether they’re minerals, fossil fuel products (plastics), or even energy that was derived from a non-renewable source. We’re also running out of space for “trash,” and the ubiquity of garbage is causing major ecosystem disruptions that threaten multiple planetary boundaries, including even circling back to us in the form of microplastics in the food we eat (“Microplastics found in human poop,” 2018). Personally, I find that the more I think about it, the more absurd it seems: most of us throw things away multiple times a day, knowing that they will be buried in a landfill and never — at least not in any human-relevant timescale — return to the earth system cycles that support life on earth.

I’m not writing this issue to sell you on trying to live a zero-waste life. We should certainly be trying to reduce waste in our own lives, but it’s very hard in the status quo and our efforts are inherently limited in scope. Instead, I’m writing this issue to call into question the basic premises of our consumer economy and to point out that far more sensible alternatives already exist and are attainable if we shift our focus to try to replicate the way natural systems use resources. We’ll read about what the idea of a “circular economy” is, we’ll explore a case study of industrial symbiosis, and we’ll read about the “right to repair” and open source hardware initiatives.

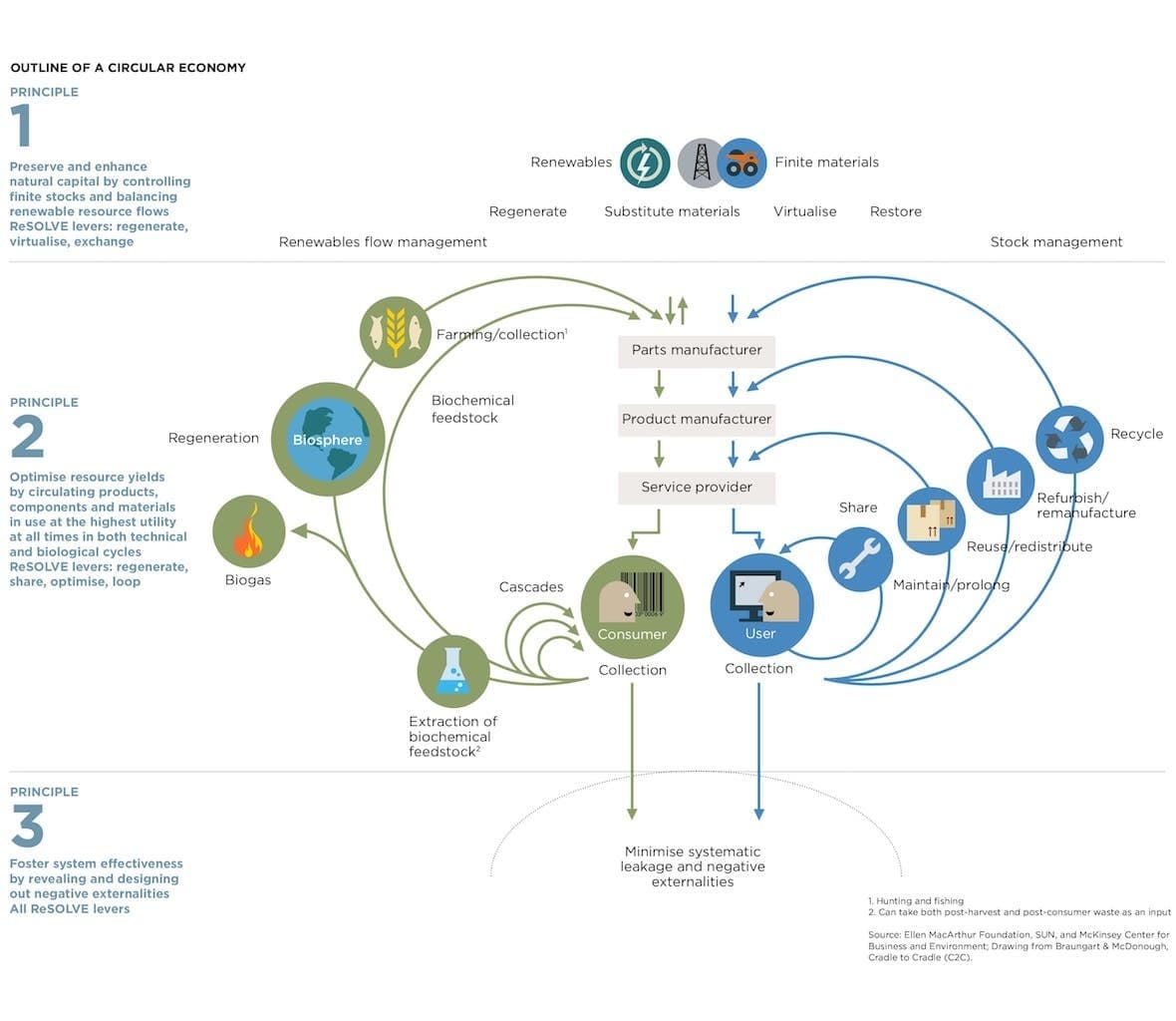

Source: Ellen MacArthur Foundation, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept/infographic

“What is a circular economy?” (10 minutes)

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s mission is to catalyze a paradigm shift in economic activity towards a “circular economy.” In this article and video, they explain the basics of a circular economy, the differences between “technical and biological cycles,” and how a circular economy can not only fulfill the needs of modern society, but can enable us to thrive through a transition to a regenerative economy. According to them, a circular economy is built on three principles: eliminating waste (through design), re-using materials, and adding value and capacity to the natural systems that support human life (read: regenerative agriculture, among other things). Together, these principles define a new approach to human society, one that internalizes the “negative externalities” of our current extractive economy and focuses on holistic generation of value for the entire system. It’s worth spending some time exploring the other pages linked from this one.

Kalundborg Symbiosis (10 minutes)

The Kalundborg Symbiosis project is a circular economics case study of industrial symbiosis located in Denmark. It’s a collaboration between municipal utilities, electricity generation, biotech research and manufacturing (Novo Nordisk), and other private companies that involves cycling energy, water, and materials including sulphur, sand, biomass, and fertilizer between the various stakeholders. It’s easy to learn about circular economies and other approaches to changing the paradigms of economic activity and assume that they are incompatible with modern industrial production (and as a result, with the modern industrialized lifestyle), but this case study demonstrates that, through deliberate design, we can take advantage of circular principals to build industrial systems that result in a dramatic reduction in resource use. It also represents an innovative partnership between public and private stakeholders; there is an oversight association called (appropriately) ‘Kalundborg Symbiosis' that is governed by the stakeholders, something reminiscent of what we talked about two weeks ago in the issue on generative economic models. The project maintains its own website and I’d encourage you to head there to play with an interactive visualization of the material flows involved. Unfortunately, the visual tool has not been translated to English, but it’s fairly communicative despite that.

“The world’s e-waste is a huge problem. It’s also a golden opportunity” (15 minutes)

This is a short article, so I’m including two other short ones under the same header to paint a bigger and more grounded picture of this topic.

Our waste of electronic products is one of the most problematic but under-discussed pieces of the modern economy. While we’re able to produce energy from “renewable” resources like sunlight, we aren’t able to build solar panels without using finite metals and minerals. Those resources play a critical role in our lifestyles and our global economy (and in any hypothetical transition to “green energy”) and it’s a role that we are currently unable to innovate away. Fortunately, and, of course, unfortunately, there are millions of metric tons (44.7 in 2016) of e-waste for us to mine for valuable deposits of gold, silver, copper, and more. E-waste is a huge problem for any number of reasons, including the impacts on human health where it is dumped (mostly Africa), but that huge problem is driving innovation and government investment in up-cycling and reuse, and open source hardware projects have sprung up across Africa to provide blueprints for turning e-waste into productive tools. The innovative approaches to e-waste management that are developing in Africa can serve as a guide for the whole world to learn how to keep extracted resources in circulation rather than discarding them only to extract more.

Right to Repair (10 minutes)

Planned obsolescence is a despicable but now-ubiquitous business practice with a fascinating history — there’s a good Planet Money podcast that delves into it. Here’s an egregious example: Apple sends out software updates that deliberately degrade performance of older iPhones. They’ve also progressively made it harder or impossible to replace batteries in their products; batteries naturally degrade, meaning that they’ve put a concrete (and relatively short) lifespan on their products.

These practices are anathema to the concept of a circular economy and to the core concepts of reducing our footprint on the earth. Instead, we need repair and reuse to be considered primary goals at the design stage. Fortunately, this is one of the few pieces of “cultural change” that has a well-defined lever that is actively being pushed: “right to repair” laws are being considered in 20 US states; “right to repair” is part of the EU’s “Circular Economy Action Plan;” even the New York Times Editorial Board has endorsed right to repair legislation (going notably further than progressive presidential candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren). By forcing companies to make allowances for consumer repair, we may be able to shift design goals towards slowing consumption and facilitating reuse of materials, reducing e-waste along the way.

Book Recommendation: Cradle to Cradle, Michael McDonough and Michael Braungart

This book (2002) introduced the “cradle to cradle” design framework, a way of thinking about societal metabolisms (i.e. production and consumption) that attempts to mimic the earth’s resource cycles. It establishes principles of design that aim to guide the development of circular product cycles, eliminating the idea of “waste” altogether. McDonough and Braungart did not invent circular economics, but they integrated the design and science of product metabolisms in a way that can be used to guide modern economic and industrial practices. Their work led to the creation of an independent non-profit, the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute, that manages international standards for “Cradle to Cradle” certification of goods. You can hear more about the Cradle to Cradle concept in this video from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe if you haven’t already and share if you have: