Sacred Headwaters #39: Divestment

Divestment has been one of the most long-lived climate movements and continues to gain momentum, but its real mechanism is subtle. How does it actually contribute to the project of decarbonization?

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and head over to our table of contents to browse the whole library. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Table of Contents

Sacred Headwaters has a table of contents intended to allow readers to “catch up” more effectively, to facilitate using Sacred Headwaters as a reference, and to give a better picture of what the newsletter is about for those who are just joining.

Issue #39: Divestment

My alma mater, Dartmouth College, announced its divestment from fossil fuels on October 8th, joining a growing wave of divestments this fall from prominent institutions and pension funds. Even Harvard, long one of the staunchest opponents of divestment, announced it would be divesting its assets from the fossil fuel industry after a ten year fight by students, alumni, and faculty — although they refused to call it “divestment.”

Dartmouth and Harvard are part of a renewed wave of institutional divestment (stay tuned for more big announcements on October 26th) and a demonstration that a campaign initiated a decade ago has grown into one of the most durable climate movements to date. It has also come to encompass a much larger range of actions than its original ask, the withdrawal of financing from the top 200 publicly traded fossil fuel companies (per Carbon Tracker’s Unburnable Carbon report).

Divestment today is an umbrella that includes traditional institutional divestment, personal financial actions like bank switching, and campaigns like Stop the Money Pipeline that use advocacy and direct action to pressure banks, insurance companies, and private equity to stop providing financing to fossil fuel expansion. It also has direct ties to on-the-ground movements like the fights against Line 3 in the US and Coastal GasLink in Canada, leveraging campaigns against financial companies to support Indigenous-led opposition to fossil fuel projects.

Despite its durability, many — including more than one of Harvard’s presidents and, of course, Bill Gates — have questioned its effectiveness, arguing that removing some sources of financing in an otherwise unchanged environment will do little to lower emissions and could actually perversely drive industry stock prices upwards in some cases. These arguments may no longer apply today as divestment has grown to attract more significant sums than anyone expected (just a few weeks ago, Quebec divested its $390bn pension fund, the 12th largest in the world, from oil), but more importantly, they misunderstand the intended purpose of divestment and fail to see its most significant impacts.

In this issue, I want to explore what activists thought they were doing when they launched divestment, what historical campaigns they were looking to, and how it has actually transformed climate discourse and mobilized a generation. This isn’t just meant as cheerleading, though I think everyone who’s been part of the divestment movement deserves as much cheerleading as they can get — it’s meant to explore the theory of change underlying an important climate campaign to help elucidate how we can build and expand upon that movement to drive meaningful climate action in the face of almost unbelievable government intransigence (in the US right now in particular).

If you’re interested in learning more about this beyond what’s included in this issue, definitely take a look at my Master’s dissertation, “Towards a Fossil Fuel Non-Cooperation Campaign,” which is, uh, a 15,000 word version of this issue.

Clarifying the divestment theory of change (10 minutes)

Stephen O’Hanlon, The Phoenix, 2014

This short piece in the Swarthmore College newspaper lays it out clearly, straight from the horse’s mouth (the US fossil fuel divestment movement started at Swarthmore in 2010). O’Hanlon responds to the common critiques of divestment and clarifies exactly how he — and divestment leaders like Bill McKibben — understand the theory of change behind it. He writes,

Divestment isn’t about reducing share prices of fossil fuel companies; rather, it is about challenging the social and political license of the industry to operate in our political system.

The seven years since O’Hanlon wrote this have mostly born his position out. The exception — and even this, he alludes to — is that the growing movement against fossil fuel financing has indeed started to take a toll on share prices and capital investment. One could easily argue that this is because of a growing understanding of the risk of fossil fuel assets becoming “stranded” and that’s true, but it’s also very likely that the shifting public narrative surrounding the fossil fuel industry is forcing the financial industry to act on this risk rather than willfully ignore it. The idea that fossil fuel assets could be a major liability in a decarbonizing world is as old as divestment itself and probably older, but only now, after the movement’s success, are we seeing real financial implications beginning to play out.

I would be remiss if I didn’t remind everyone that when O’Hanlon refers to the failure of the 2009 cap and trade bill in the US, he is referring to the bill that coal baron Senator Joe Manchin shot with a rifle.

Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: what does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets? (20 minutes)

Atif Ansar, Ben Caldecott, James Tilbury, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, October 2013

Executive Summary, pp. 9-18

O’Hanlon cites this report in the previous piece. It is an investigation of the potential impact of the (at this time relatively young) fossil fuel divestment movement on the industry and related financial assets. It’s an interesting read for a variety of reasons. First, it references literature on historic divestment campaigns, something that’s conspicuously missing in most mainstream coverage of the fossil fuel divestment campaign. It turns out, unsurprisingly, that these campaigns — against Apartheid in South Africa, against the tobacco industry, and others — were almost universally successful in driving government action to restrict the target industry or regime.

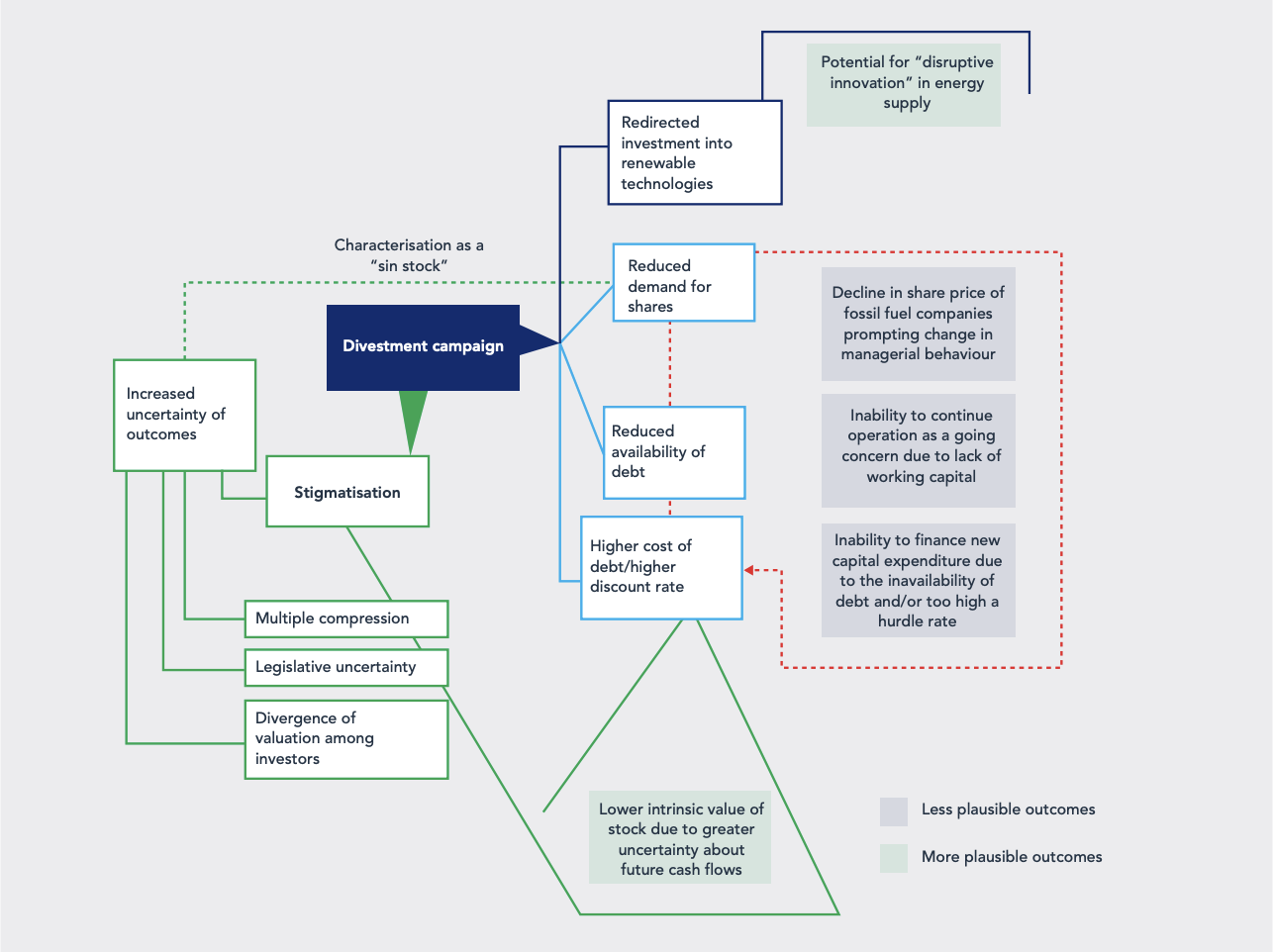

Second, the report lays out (as in the figure below) a broad picture of the variety of mechanisms by which divestment might have an impact. It correctly emphasizes the importance of stigmatization as a mechanism of action and explores how that stigmatization can actually lead to the desired more material goals of the campaign. Among other things, the authors note that stigmatization can lead to “suppliers, subcontractors, potential employees, and customers” refusing to work with the industry; to shareholder activism; and to shifting norms within the investment community initiating feedback loops that will ultimately deflate the “carbon bubble” of stranded assets — all of which are happening with increasing momentum today.

Without a doubt, stigmatization has been divestment’s core project, and it’s progressed significantly — in fact, like tobacco CEOs before them, oil executives will be testifying before Congress about their decades of climate denial this month. But it’s becoming increasingly clear that the report may have been wrong about the limited direct impacts of divestment, even if that mechanism was never considered the core purpose of the movement. The report argued that “the plausible upper limit of possible equity divestment” would be $240-$600 billion “and about another half that for debt.” Today, more than 58,000 institutions have committed to divest nearly $15 trillion dollars, and activist campaigns against banks (and insurers) are transforming the debt financing landscape as well. The French bank La Banque Postale announced last week that it will be completely withdrawing from oil and gas finance by 2030.

Table 3 (p. 40) and Table 5 (p. 64) are worth looking at as well because they contain information about historic divestment campaigns.

Fossil fuel divestment: theories of change, goals, and strategies of a growing climate movement (30 minutes)

Luis Hestres & Jill Hopke, Environmental Politics, 2019

This paper is an interesting look at divestment from two angles. First, it includes a more up-to-date literature review of research that’s been done on divestment, looking at the campaign’s history, the political context from which it emerged, and how it fits into a broader strategy of climate action and activism. As part of this, the paper notes something important that I don’t think gets enough attention: divestment and its associated campaigns have worked to refocus public discourse on the supply side — on limiting fossil fuel production. Yes, demand matters, and yes, of course we need to pursue efficiency and electrification (far faster than we are) — but as the UNEP Production Gap reports and others have noted over the years, production must go down if we have any hope of limiting warming even to 2C. That simply wasn’t part of the discourse ten years ago, and I believe that the divestment umbrella of campaigns has played a critical role in changing that.

Second, the paper interviews a variety of climate activists (if you’re engaged in the US climate world, you’ll recognize many of the names) to try to understand how they perceived the “theory of change” underlying divestment. This section speaks to the fundamental misunderstanding that many of divestment’s critics (like Gates) seem to have. Activists see divestment as an organizing tool designed to drive change by leveraging an understanding of how political change happens and building the power needed to effect it. If you see climate as a purely technical or instrumental problem, that won’t make sense to you, but I’d like to think that it’s becoming increasingly hard for most to conceptualize climate in that way as we’ve so utterly failed to respond over four decades. Once you recognize that climate inaction is the result of political and social (or power) dynamics, the need to draw from established patterns of social movement organizing that have overcome problems like this in the past becomes clearer. The interviews with activists in this paper demonstrate that’s exactly how the core organizers who have played a role in the divestment movement see it.

Hestres has a short piece in The Conversation that positions divestment within a broader strategy fighting against new fossil fuel infrastructure; it’s not a summary of this paper but it references it and is interesting as well.

Like what you’re reading here?

Sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue and consider forwarding this email to a friend or colleague.

Nick, have you divested your retirement funds? I like that this is action-oriented.