Sacred Headwaters #34: Net Zero...or Not Zero?

The last few years have seen rapid growth in both net zero commitments and net zero’s prevalence in global discourse. Is that good, or is net zero functioning as a "discourse of delay?"

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and head over to our table of contents to browse the whole library. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Table of Contents

Sacred Headwaters has a table of contents intended to allow readers to “catch up” more effectively, to facilitate using Sacred Headwaters as a reference, and to give a better picture of what the newsletter is about for those who are just joining.

Issue #34: Net Zero…or Not Zero?

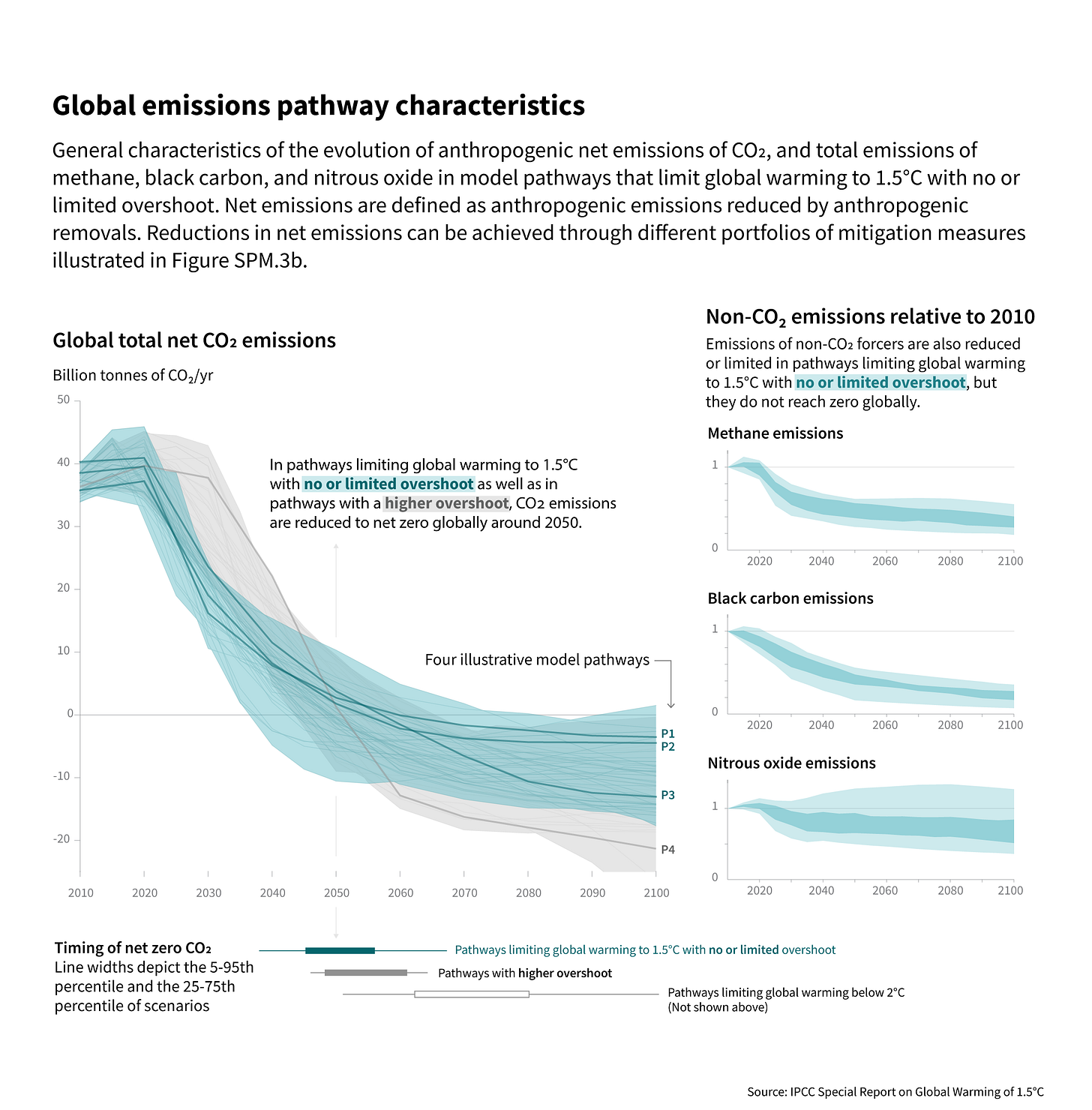

The last few years have seen rapid growth in both net zero commitments and net zero’s prevalence in global discourse. 61% of global emissions are now covered by net zero commitments! That’s pretty good, right? Reaching net zero means, effectively, “anthropogenic GHG emissions - GHG removal = 0.” If anthropogenic emissions were zero, we’d be at “net zero” regardless of whether or not we were actively removing GHGs, but the phrase is generally used to deliberately incorporate GHG removal (“negative emissions technologies” — see issue # 5). It makes intuitive sense: human-caused emissions raise the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere which in turn increase radiative forcing (trap heat); if we bring human activity to “net zero,” we stop increasing forcing and stop global warming. There’s some delay, and of course there are always questions about how the Earth’s “natural” carbon cycles are changing due to human activity, but the gist of it is pretty straightforward: achieve net zero and the Earth stops warming.

Here’s the thing: we’ve had international agreements on climate change since 1992. And we’ve had a variety of different ways of committing to and tracking progress ranging from atmospheric GHG concentrations (“350 ppm”) to percentage cuts in emissions (“12.5% below 1990 levels”) to carbon budgets (the UK carbon budget for 2018-2022 is 2,544 MtCO2e). Only in recent years, after the Copenhagen Accord and Paris Agreement established temperature limits (+2C, +1.5C respectively) as policy goals, has “net zero” come to be prominent. It’s scarily easy to lose sight of things like this, but “net zero” is a new way of conceiving or framing climate mitigation.

Is it working?

The growth of commitments certainly seems positive. As mentioned, 61% of emissions are covered by net zero commitments. They vary greatly in their plausibility, but it’s hard not to see widespread commitment to climate mitigation, regardless of its veracity, as a step forward, at least for those of us based in North America.

On the other hand, Shell has committed to net zero by 2050. Their plan involves achieving net zero by using natural sinks ('“planting forests the size of Spain”) and expanding carbon capture and storage to scales never before seen. BP has a “plan” too. Both companies intend to continue producing oil and gas through the middle of the century and beyond; Shell explicitly intends to scale up methane (“natural”) gas production over the coming decades. While it’s true that BP and Shell’s operations — the extraction and processing of gas, coal, and oil — are significant sources of emissions today, the burning of fossil fuels is the single largest contributor to climate change. (As a side note, the burning of fossil fuels is also responsible for millions of deaths every year — more than 8 million in 2018). These companies claim that they can continue producing fossil fuels for consumption while achieving “net zero,” and while this should be obvious, I’ll say it anyway: reducing (or even eliminating) the emissions involved in the production of fossil fuels does not eliminate the emissions that are created by burning them.

As another example, Mark Carney, former head of the Bank of England, recently claimed his asset management company was net zero because their “enormous renewables business” offset their fossil fuel investments. He was forced to walk that claim back by public outcry, but it speaks to the way the term is being used.

So with the world increasingly awash with net zero commitments that involve continuing to pursue (or even grow) the single activity — burning fossil fuels — that’s most responsible for the climate crisis…perhaps we should take a step back and assess whether “net zero” is actually a valuable tool or whether it is functioning as a terrifyingly successful “discourse of delay.”

There are some very practical questions about net zero, some of which can help guide more successful commitments, and organizations are working on establishing criteria and assessing commitments. There are also big questions about the feasibility of negative emissions technologies and the scale at which they can be relied on to achieve the “net” aspect of net zero (issue #5, and we’ll probably go deeper on this at some point). In this issue, we’re going to look at net zero’s rapid rise in prevalence, how likely it is to lead to meaningful reductions in emissions, and what pitfalls it might have. Commitments from Shell and BP, from Canada and Mark Carney, and from many others, suggest that it’s not working. Does it just need to be fixed, or is it the wrong approach?

Taking Stock: A global assessment of net zero targets (10 minutes)

Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit and Oxford Net Zero. Time is based on just reading the executive summary and conclusion.

This report is an in-depth review of existing (March 2021) net zero commitments globally. As the authors note, these commitments have grown rapidly over the last few years and vary greatly in their content. Of the 769 net zero targets they found amongst nations, subnational regions, corporations, and large cities, 20% of these meet a set of robustness criteria that indicate they may actually be on track to achieve their goal. While the report notes that there are some issues with the prospects of large growth in negative emissions, their main focus is on whether or not the net zero commitments themselves are plausible, not on whether net zero is the appropriate goal. The report lays out some of their robustness criteria and gives a few examples of well-designed net zero plans. As more and more actors develop net zero plans, it’s important that the world holds them to account, and the report explicitly calls out the problems with Shell and BP’s net zero commitments.

Sweden, notably, established a net zero by 2045 goal in 2017 (quite early) and has a series of legislative requirements that demand revisiting climate plans and targets regularly. Anomalously, Sweden’s net zero target incorporates both emissions reduction targets and limits to the use of offsets, effectively separating the goals of “emissions reduction” and “negative emissions;” this report doesn’t speak to that in much detail, but it’s a transformative twist on net zero that makes it much more powerful that we’ll read about more below.

Which countries have a net zero carbon goal? (5 minutes)

This is a list of national net zero commitments globally and specifies what type of commitment each one is — is it legislated? A stated commitment? A UN pledge? It’s kept up-to-date and is a good reference. The notes provide some useful context and it’s interesting to compare and contrast the countries with legal commitments and interim targets with those who have simply made vague, far-off statements about it. I know I’m expressing a lot of skepticism in this issue, but it is genuinely inspiring to see how many countries have made serious legal commitments, though they tend to be smaller ones.

Not Zero: How 'net zero' targets disguise climate inaction (20 minutes)

ActionAid International and a coalition of other non-profits including Friends of the Earth International and Corporate Accountability.

The global assessment report above indicated that 20% of the large-scale net zero commitments they reviewed appeared legitimate or “robust” and recommended pathways for other net zero commitments to reach similar robustness. Unfortunately, if only 20% are “robust,” that leaves 80% seriously lacking. This report looks at those 80% and suggests that rather than being victims of vagueness, the actors making these commitments are weaponizing vagueness to delay meaningful emissions reductions. They pull no punches:

Far from signifying climate ambition, the phrase “net zero” is being used by a majority of polluting governments and corporations to evade responsibility, shift burdens, disguise climate inaction, and in some cases even to scale up fossil fuel extraction, burning and emissions. The term is used to greenwash business-as-usual or even business-more-than-usual. At the core of these pledges are small and distant targets that require no action for decades, and promises of technologies that are unlikely ever to work at scale, and which are likely to cause huge harm if they come to pass.

It’s worth noting that the authors of this report believe we must be striving for “real zero” — zero GHG emissions at all — by 2030, a position that is far from the IPCC consensus. I generally lean in that direction as well, and of course, no scientist would disagree that the sooner we eliminate GHG emissions, the better, but it’s worth being aware that this critique of net zero is coming from a group that demands far more radical action than the mainstream climate discourse. That said, their core critiques apply whether you think real zero by 2030 should be a goal or not. Their emphasis on the problems of international offsetting that are central to most global North net zero targets and the resultant risk of “carbon colonialism” is really powerful; we are effectively pushing the responsibility for meaningful change onto the people who hold the least responsibility for climate catastrophe.

One other thing I’ll mention: they briefly talk about how net zero claims often embrace or imply temperature overshoot, the scenario where we blow past our temperature target (+1.5C) and then cool back down to it in the subsequent decades through carbon removal. I expect this concept to become much more prevalent and publicly accepted as net zero targets spread in a self-reinforcing discursive cycle: if temperature overshoot is acceptable, then net zero makes plenty of sense as a goal, and if net zero is our goal (with the assumption we’ll then trend negative), then temperature overshoot is reasonable. These ideas aren’t new — they’ve been built in to various climate models and socioeconomic pathways for a long time — but they’re new in the geopolitical discourse, and unfortunately, our outcomes are defined more by the political economy of climate decision-making than by science, so these are important developments to pay attention to.

The problem with net-zero emissions targets (10 minutes)

Duncan McLaren. This is a summary post about a paper McLaren et al wrote in 2019.

In this article, McLaren digs into what I think is the most fundamental problem: net zero encompasses two axes of mitigation, emissions reduction and negative emissions technologies, and it makes no inherent commitment regarding the balance between those two. That uncertainty allows for the wide range of possible “net zero” commitments that we’ve seen, including those from oil majors like Shell and BP and countries like Canada who continue to scale up oil and gas production while embracing the net zero discourse. McLaren also explores some of the subtleties that compound this uncertainty: IAMs and other socioeconomic climate models virtually all incorporate vast rollouts of NETs and actually favor them over emissions reduction because of the way they discount future costs in calculations. These models, like the “net zero” claims of today, make no distinction between emissions reductions and negative emissions. McLaren argues that we need to separate the two, both in modelling and in target-setting, creating dual targets for emissions reductions and for scaling up negative emissions. As noted earlier, Sweden’s net zero commitment takes steps towards this, although it’s not quite in line with the full separation McLaren calls for here.

A brief history of climate targets and technological promises (15 minutes)

Duncan McLaren. This is a summary post about a paper by McLaren and Nils Markusson from 2020.

This paper isn’t specifically about net zero, but it speaks to something I’ve been alluding to throughout this issue: global climate targets, preferred mitigation strategies, and technological developments do not develop independently. McLaren and Markusson argue that over the decades since the creation of the UNFCC, the global community has moved haphazardly through a variety of climate mitigation goalposts and that these goalposts are the result of the “coevolution of technological promises, modelling techniques and political aspirations.” As an example, the IPCC produced a report on carbon capture and storage (CCS) 2005 after which CCS was incorporated into the IAMs…the cost optimization built into IAMs then selected for high levels of CCS, leading us to a world in which every IPCC scenario for +1.5C involves significant use of NETs. (Sidenote: here’s a fascinating looking paper along these lines arguing that IPCC “pathways and scenarios have a ‘world-making’ power”). The point here is one that’s often either missed or ignored: discourse, research and technology, and the political realm exist in a constant interchange, influencing and being influenced by each other. As much as we all might wish it was “just about the science,” even the science isn’t just about the science, as evidenced by the recent controversies around solar geonengineering research (Swedish balloon test controversy, US National Academy of Science / NYTimes controversy). The net zero target might seem like it’s just a way of tracking progress, but its structure is influencing how we pursue that progress in the first place.

To be abundantly clear: I highly recommend this article. 13/10.

Like what you’re reading here?

Sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue and consider forwarding this email to a friend or colleague.