Sacred Headwaters #29: International Debt

International debt and institutions like the IMF and the World Bank have played key roles in the world's least developed countries over the last 70 years. Who do these roles benefit?

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and head over to our new table of contents to browse the whole library. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Table of Contents

Sacred Headwaters has a rudimentary table of contents intended to allow readers to “catch up” more effectively, facilitate using Sacred Headwaters as a reference, and give a better picture of what the newsletter is about for those who are just joining us.

Issue #29: International Debt

Apologies for the unannounced break over the holidays! I took some much-needed time away from the computer.

This issue is the last in a series of four newsletters focused on debt. In this series, I’m trying to build a narrative that emphasizes how important debt is as a cultural, political, and economic construct in the broader challenges of achieving a sustainable and equitable civilization, and how important it’s been to structuring the unsustainable and unjust society we live in today.

Issue #29: International Debt (Jan 18, 2021)

International debt is a big concept, and it’s one that’s hard to understand without talking about the geopolitics and growth of global capitalism in the post-war era. The sovereign debt of the so-called developing world and the associated international development institutions created after the end of World War II were instrumental in the Cold War fight to “stop the spread of communism” at an ideological level. But that ideological level is inseparable from the way the Global North used these same tools to ensure cheap access to labor and natural resources and to create new markets by facilitating the expansion of global trade and the reach of US-based corporations. Debt — and institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and WTO — was (and continues to be) one of the tools used for this purpose. It’s of course not the only tool, and it doesn’t take much digging to learn about US-orchestrated military coups that were closely tied to or followed by US-based business expansion in those countries, but that’s a story for another time.

As is probably clear, international debt is integrally tied to global political economy and the ideologies of globalization and, more recently, neoliberalism. The reading in this issue is going to introduce and explain the mechanics of the debtor relationships between the Global South and the Global North and some of the ways those relationships are leveraged to produce conditions that ultimately benefit the Global North. How much money flows from the Global South to the Global North through debt servicing? How do the IMF and World Bank use debt and “structural adjustment” to enforce Western development ideals, and how do those tactics end up impacting the people in the Global South?

International debt — or sovereign debt — is held by virtually all countries around the world, Global North or Global South. But as we read about in issue #27, whether or not you subscribe to modern monetary theory, the reality is that “debt” for countries with high degrees of monetary sovereignty — which includes all the colonial powers outside the Eurozone — is not a big concern. The US government can’t be leveraged by China because of the treasury bonds that China holds, despite the frequent political rhetoric from both sides of the aisle implying that. But if a country borrows in a foreign currency and their own currency doesn’t have the exchange rate stability required to pay the foreign debt, then default becomes a real concern. This macroeconomic situation corresponds to a power dynamic: countries with high degrees of monetary sovereignty, like the US and Britain, are holding all the cards, while Global South countries find themselves in debt relationships that can be used as leverage. This relationship is what we’re going to focus on in this issue, which is why we are focusing on how international financial institutions (IFIs) like the IMF operate in these circumstances.

The Development Delusion: Foreign Aid and Inequality (25 minutes)

In this paper, Jason Hickel outlines the geopolitical and economic history of international development over the last century, painting a picture of an empowered Global South in the immediate post-war era that was hamstrung first by a “regime change” campaign (orchestrated primarily by the US and Britain, along with other colonial powers), then by a macroeconomic crisis that set the stage for structural adjustment. While much of Hickel’s piece isn’t specifically about debt, it gives us the context we need to understand how and why Global South debt came to be leveraged the way it has been over the last 40 years. He also speaks to an aspect of debt separate from the neoliberalization dictated by structural adjustment: the ongoing outflow of capital from the Global South to the Global North. While there are critiques of some of the studies he cites about illicit financial flows, the costs of debt servicing are very real, and debilitating. Ultimately, Hickel situates debt and the world’s international financial institutions (IFI) within a decades-long effort by the world’s colonial powers to re-create the extractive conditions of the colonial era with new, more subtle arrangements.

As unlikely as it might seem, I wrote the introduction to this issue before coming across this paper, but it seems that Hickel and I see these issues in similar ways.

The IMF: A Cure or a Curse? (15 minutes)

This more balanced piece by Devesh Kapur gives a good overview of the IMF’s history, how its loan programs and structural adjustment programs work, and how its scope and power has changed over time. For its first three decades, the IMF was primarily an “exchange rate stabilization” institution — during the period that Hickel called “developmentalism” — but the end of the gold standard in 1971 initiated significant changes in the IMF’s mission, and by 1980, it had effectively become a bank for the developing world. As the IMF grew and responded to a series of debt crises in Global South countries, starting with the Latin American debt crisis in 1982, the scope of its loan programs — and of its mission — grew. The IMF started using Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) — specific sets of conditions prescribing economic policy attached to loans — to force financial liberalization, privatization, and openness to trade. Kapur is less blunt that Hickel in this department, but still suggests that in many ways, the IMF was effectively doing the bidding of the private financial sector with a variety of negative effects on both the countries themselves and the stability of the broader financial system. He closes with a handful of suggestions for improving IFIs and international credit, but notes that, for the most part, these suggestions aren’t in line with the interests of the stakeholders with the most power — countries like the US — and are thus quite difficult to implement.

A Brief History of Resistance to Structural Adjustment (5 minutes)

This is basically a laundry list of protests, strikes, and general unrest in Global South countries as a response to IMF-originated structural adjustment programs up through the year 2000. I share this not because there’s a particular insight to glean here, but because the devastating impacts of Western international policy are so often invisible to the citizens of the countries perpetrating those policies. The events recorded in this document span from workers’ and student strikes to Indigenous protests to military coups, but they were all initiated by austerity and privatization measures demanded by the IMF. It also includes information about police murder of protestors, a common but not universal feature, and while I would certainly not claim that the IMF encourages police violence, it’s not an unreasonable reach to draw a connection between the interests of global capital (as represented by the IMF) and state violence.

Unhealthy conditions: IMF loan conditionality and its impact on health financing (20 minutes)

The whole report is about an hour of reading. I’d recommend the Executive Summary, Section 1, the Conclusion, and ideally the majority of the “Box” figures which delve into specific examples of IMF conditionality and its results.

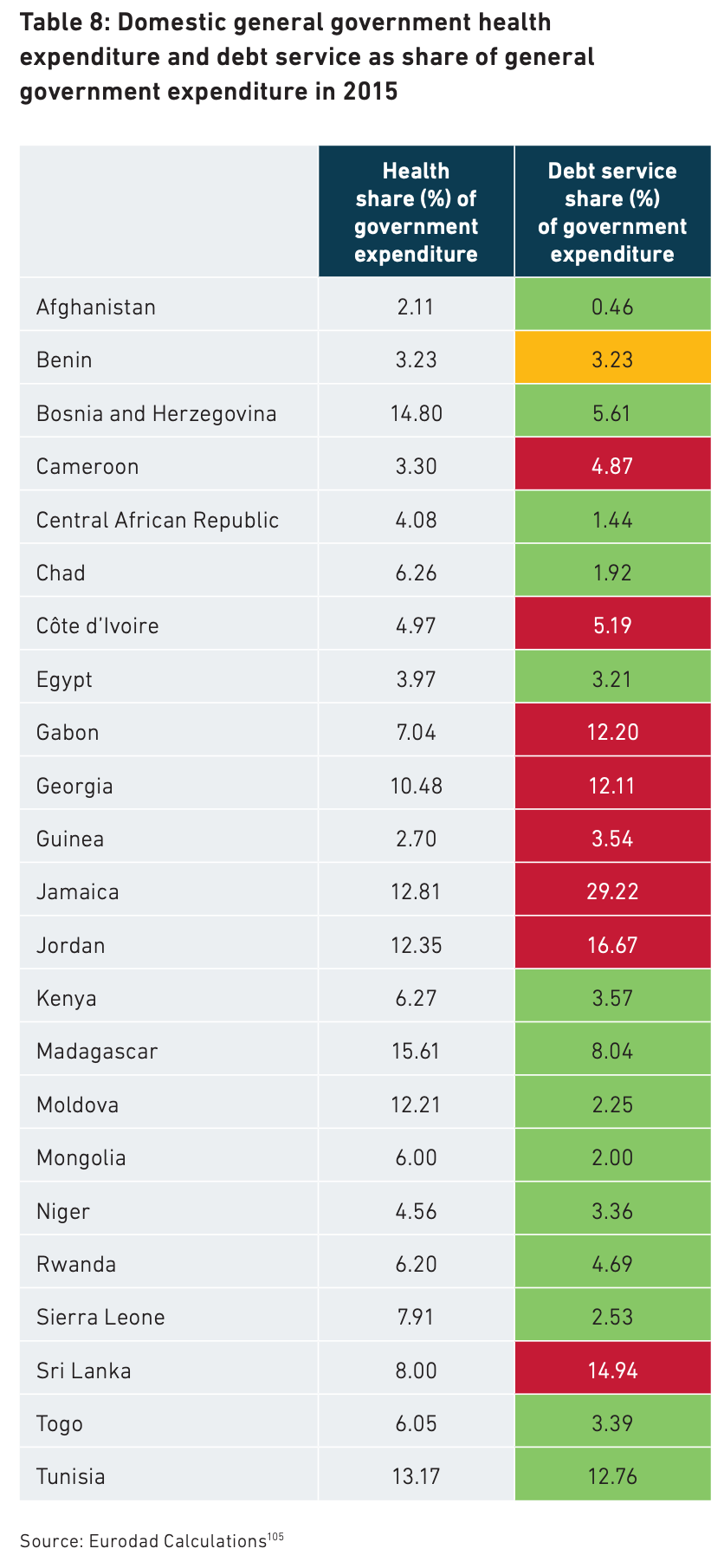

Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) are generally talked about as being used from the 1980s through the early 2000s. Beginning in the early 2000s, the IMF — in response to broad criticism about the failures of its SAPs — began reviewing and re-working the conditionalities associated with its lending programs. Today, the IMF regularly uses language focused on inclusive and equitable growth and respecting national sovereignty, implying that its approach to lending has changed. This report argues that, while the language has changed, the praxis has not, and if anything, in recent years, lending conditionality has started trending upwards. The report looks at IMF loans made over the years 2016 and 2017, assessing the attached conditions and finding that austerity, financial liberalization, and privatization remain core components of IMF lending policies. An additional note that lines up with one of Hickel’s points in today’s first essay is that IMF lending programs — in the interest of protecting creditors, including themselves — force countries to prioritize debt service payments over social services. The report found that the “crowding out” effect this has, specifically on health care spending, is significant. While the earlier authors in this issue recommended democratization of IFI governance, this report focuses on the mechanics of lending (something that would undoubtedly follow from more democratic governance of the IMF), arguing for a stronger focus on debt restructuring rather than new lending.

Like what you see?

Sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue.

Sacred Headwaters relies on word of mouth to reach more people. Tell your friends!