Sacred Headwaters #14: "Defund the Police"

Policing as we know it today has not always existed -- it's a modern construct and it's important to understand why it exists, if it needs to exist, and whether reform is possible as we move forward.

Sacred Headwaters is a bi-weekly newsletter that aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come. If you’re just joining us, consider checking out the first issue for some context and read through the other issues when you can. The newsletters are not strictly sequential, but this exploration is meant to build on knowledge and understanding over time. Subscribe below if you haven’t already, and please share with friends, family, and colleagues who may be interested:

Issue #14: “Defund the Police”

A practical note: I’m publishing this issue a week early because of the urgency of this discussion. The next issue will come out two weeks from now, meaning the schedule is shifting weeks.

When environmentalists talk about "climate justice," the phrase typically refers to how marginalized groups are more negatively impacted by the effects of climate change than rich white folks. This is obviously true, and the same applies to COVID-19 and any other number of systemic problems. But I see justice -- and climate justice -- much more broadly than that.

We've been talking about police violence and systemic injustice for years. Year after year, videotaped murder after murder. But it doesn't get better, despite many people's genuine intentions to make it so. We've been talking about climate change for decades, too, and have not made a dent.

These crises have a shared cause: a system that's built on extracting value for the few, from the many and from the landscapes we live within. Overwhelmingly, ‘the many’ have been the global South; Black Americans; Indigenous peoples. This international system was built from the ground up over five centuries of imperialism with an explicit purpose: convert life and labor into wealth with no regard for the human cost involved.

We have an opportunity to change one of the foundational pillars of that imperial system right now; the “Overton window,” the window of what’s perceived as politically possible, has rapidly expanded in a matter of days.

With that in mind, I think it’s important for us to look at the institution of policing through a critical lens guided by these basic questions: why does it exist? Can it be reformed? And, does it need to exist? Concurrently, why do many of us assume it needs to exist? If your immediate answer is, “of course we need police” — I’d ask you to step back from dismissiveness and disbelief and take a deeper look at your own assumptions. Why do you feel that way, and what’s so convincing about the evidence (is there any?) for it that we can’t even entertain alternatives?

“Defund the police” is a demand that’s spread rapidly across the West in the last week. But it’s not a reactionary new concept, despite the way traditional media is reporting on it. It’s one that critics of the criminal justice system have been exploring for many years. It’s sudden ubiquity could easily be lost under the banner of “criminal justice reform” as part of a strategy to appease the public while maintaining the status quo, so let’s take this opportunity to learn about it and determine for ourselves whether or not it’s “realistic” and what its impacts on public safety, the alleged goal of of the institution, might be. Those in power cannot be trusted to make this determination.

I want to be explicit for non-US readers: there may be some examples of effective alternatives to policing around the world, but this is not a uniquely American problem. Systemic racism and militarized police forces are tools of an imperial system that has colonized most of the globe. Stand with those on the front lines in the United States, but don’t turn a blind eye to the violence in your own home.

“The Price of Defunding the Police” (20 minutes)

Everything from preschool programs, to summer jobs for youth, to improved access to healthcare are more clearly linked to reduced crime rates and community development than police, jails, and prisons.

This article summarizes and expands upon a report, “Freedom to Thrive,” published by a group of organizations led by the Center for Popular Democracy. The report looks at public safety, policing, and budgets in the context of 12 major cities and counties in the US. I’d strongly encourage you to read the report’s introduction and conclusion in addition to this article (and if you live in one of the cities in question, definitely read that section as well), but the article provides a good overview. The report argues that there is a large body of evidence suggesting that every dollar spent on supportive services — community investment — has a far greater marginal impact on crime reduction than the same dollar spent on policing. The secondary piece, of course, is that every dollar spent on militarizing a police force is a dollar that reinforces existing racial injustice in the most vulnerable communities. The vision of “defunding the police” that the Center for Popular Democracy advocates for is a strategy they call “divest/invest” — it’s not about outright abandoning public safety. It’s about spending money on public safety where it actually makes a difference and withdrawing it from institutions and practices that cause harm. The author of the article lays out the report’s arguments well (and includes a variety of other supporting references), but tries to offer a more balanced perspective, pointing to things like state Medicaid expansion as alternative ways to fund mental health support (as opposed to withdrawing funds from the police). To me, this reads as a “yes and” type of argument.

Are Prisons Obsolete? Chapter 1 (20 minutes)

In chapter 1 of this book, Angela Davis lays out the history of the rapid expansion of the American prison system, drawing ties between corporate profit motivation, arguments for rural economic development, and the criminalization of poverty. It’s impossible to talk about defunding police without also discussing the mass incarceration crisis. The US imprisons 2.3 million people nationwide and has a far higher rate of imprisonment than any other country. 113 million people have an immediate family member who has been to prison. It likely goes without saying (but should still be said) that people of color are overwhelmingly overrepresented in these numbers (and yes, the same is true in Canada and other countries). Davis’s book calls for readers to ask why; to open their minds to discussions about what the purpose of prison is and whether it fulfills that purpose. This is a salient message for me, and it’s the same question I’m calling on my readers to ask. I’ve found, over the last few days, that discussions about police funding quickly deteriorate as people refuse to engage when you raise the question of whether or not the criminal justice system as it exists today may not be the best solution for the question of public safety.

“The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration” (60 minutes+)

Apologies, this issue is going way over the one hour mark. Read this anyway.

This long-form piece by Ta-Nehisi Coates is a sweeping history of racial injustice and the policy of incarceration in the United States. He draws powerful parallels (complete with eerily similar quotes) between the arguments used by slave-owners to moralize their treatment of Black Americans and the arguments used by modern-day politicians (on both sides of the aisle) to justify mass incarceration. It’s filled with powerful first person accounts of the impacts of the prison system and statistics that are horrifying to the point of disbelief, presenting a narrative of politically mandated racial injustice that has changed names but not significantly changed course over the last two hundred years. This piece is important reading for beginning to understand that systemic and historically inescapable racial violence is endemic to the very mission of our institutions of “justice.”

MPD 150 Report: The Future (10 minutes)

The Minneapolis City Council just pledged to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department citing a structural legacy of racism that could not be reformed. So what’s next?

The MPD 150 Report was produced by the citizens of Minneapolis to assess how to achieve structural and meaningful change in policing. The whole report is interesting, particularly the historical (150-year) lens they take to assessing the MPD, but in this section, they talk specifically about how Minneapolis might transition to a police-free future. It is obvious to them — and to most of us, I think — that defunding the police completely, tomorrow, would not be an effective answer. Instead, they ask the question, which (if any) emergency calls warrant an armed respondent? The answer, it turns out, is very few; a wide variety of calls would be better dealt with by trained social workers, domestic violence advocates, or others. The report recommends transitioning investment over time to crime prevention, not through armed deterrence (i.e. with a militarized and militant police force), but rather through community development, education, and more.

Book Recommendation: The End of Policing, Alex Vitale

This book is currently being given away for free at the above link in e-book format by the publisher. Professor Vitale has been appearing in a variety of podcasts and interviews over the last week any of which can give a quick introduction to his work: here’s one from NPR.

In this book, Alex Vitale, a professor of sociology and the Coordinator of the Policing & Social Justice Project, lays out an exhaustive picture of the modern institution of policing — where it came from, the concrete effects it has on marginalized communities, and whether or not it “works” from a public safety standpoint. He also looks closely at the idea of criminal justice reform, something that sees a round of public interest after every high-profile police shooting. Real reforms have been tried around the country; the Obama administration even supported a national effort at police reform, stimulating a widespread campaign of bias and de-escalation training and more. Unfortunately, the data demonstrate that these reforms don’t work, and Vitale provides a comprehensive picture of both what’s been tried and what’s changed as a result (not much). Finally, he looks to alternatives: if the goal is to reduce crime and injustice, how can we achieve the same goals without the problems that policing brings? Can we in fact do a better job by using non-violent alternatives? This book makes a strong case that the answer is yes.

Another note: I chose this book because of its focus on policy and data-driven research; I think that’s an important piece of the puzzle at this moment in time. That said, I’d encourage readers to peruse this reading list from Verso that has many more powerful books and accounts written by Black and Indigenous American authors. It’s very hard for those of us who are white to understand what life is like in America for other people and it’s critically important that we listen to and empower the communities that are marginalized rather than operating as though we “know what’s best for them,” perpetuating patterns of patriarchal colonization.

Want to have some influence on future newsletters? I’m looking for feedback to help me understand how I can better facilitate conversations and empower my readers. If you already responded, thank you!

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe if you haven’t already and consider sharing it with friends, family, and colleagues:

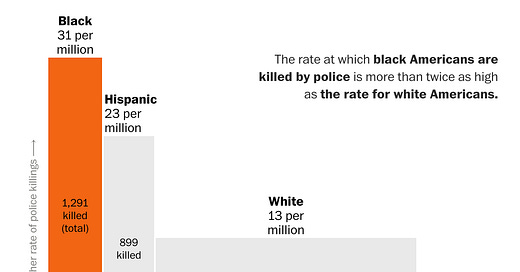

Source: Washington Post Police Shootings Database. Interestingly, while this is one of the most commonly cited references on police killings, it is significantly incomplete and deliberately difficult to determine.