America, Trump, and the Fight Against Climate Change

Trump doesn't believe in climate change. But what does the climate record of the presidents who did "believe science" say about the value of that belief in the political economic context of the USA?

Sacred Headwaters was originally a more educationally focused newsletter with bi-weekly issues that aimed to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity, about the power structures blocking change, and about how we can overcome them and build a future in which all of humanity can thrive. The format and frequency have changed, at least for now, but you can browse the resources in earlier newsletters using the table of contents. Many of the issues I continue to write about have been covered in a more pedagogical style in earlier issues.

Trump and much of his coalition openly deny the reality of climate change. This seems bad: the United States is, after all, the world’s largest historical emitter, its second largest present-day emitter, and its most powerful hegemonic actor, and the world is warming more rapidly than ever as we sail past the internationally agreed upon “safe” limit of 1.5ºC. The response of the liberal left in North America has been to bemoan the upcoming four years of climate inaction under this new reactionary, science-denying regime. Bill McKibben put it emblematically in his first newsletter after the election: “For the next few years the best we can hope is that Washington won’t manage to wreck the efforts of others.”

But this characterization of Trump’s climate denial as a departure from the previous four decades of US policy obscures more than it illuminates. Crucially, it obscures the fact that the US has been the single state actor most responsible for empowering and entrenching the fossil fuel industry in the 20th century and, more recently, for undermining international climate action at all scales. Every single president since the formation of the UNFCCC in 1992 has “believed in climate change” in the same sense that Trump does not, but here we are, 33 years later with emissions higher than ever; oil, gas, and coal production higher than ever; and an international climate framework left in tatters in the rubble of Gaza, the mirage we once knew as the “international order.”

Trump’s election doesn’t represent a break in an otherwise gradual but steady story of progress on climate change; instead, it represents an opportunity to break free from the obfuscatory idea that liberal capitalism was making any progress at all. We can now be honest about where we are and where we have to go precisely because Trump himself is forthright about the workings of the system he now oversees. In this article, first, I’ll review the current state of the climate and the question of “progress” and energy transition. Second, I’ll look at the history of American recalcitrance in global climate negotiations and its aggressive embrace of fossil fuel production at home and abroad across partisan lines. Third, I’ll speak to the political economic reality of US-based fossil capital, its role in both the domestic and international realms, and the importance of fossil fuels to the US-led world system. And finally, I will answer the argument pushed by many left liberal ENGOs during the election: that it would be better, as climate activists, to fight Harris than Trump, arguing instead that the veneer of US liberalism has been demonstrably effective at coopting and preventing the kind of radical anti-systemic movement we actually need if we hope to mitigate climate change in any meaningful sense.

The State of the Climate

This is perhaps getting cliché, but it’s worth the reminder: more than half of the cumulative emissions of the modern era have been emitted since the publication of the first IPCC Assessment Report in 1990. In fact, this oft-cited statistic can now be pushed up to 1994, just three years before most of the world agreed to the Kyoto Protocol. Depending on who (and how) you ask, the world has now warmed by 1.5ºC and the idea that we can limit warming to that temperature is, as Dr. James Hansen put it in 2022, “pure, unadulterated hogwash.” Just ten years ago, limiting warming to 1.5ºC — or at least, “well below 2ºC” — was established as the global goal not for 2025, but for 2100. I’m not going to go into details here, but part of the reason we’ve crossed this threshold 75 years early is because scientists didn’t understand certain aspects of the climate system in 2015, causing them to underestimate the rate of warming and, at least according to Hansen, the earth system’s climate sensitivity more generally.

The most fundamental reason we’ve crossed this threshold so much earlier than hoped, though, is simple: emissions have continued to rise. Emissions are in fact higher than they have ever been (and atmospheric GHGs are rising more rapidly than ever before), despite optimistic news coverage that suggests, year after year, that we have reached a peak (2024, 2023, power sector emissions in 2022, 2019, 2015, 2014). These claims haven’t been right yet, and indeed, the IEA’s latest report on coal found that global consumption set a record last year, with both thermal coal and metallurgical coal use increasing by about 4% to nearly nine billion tons. Coal is the fuel source that powered the British industrial revolution, supposedly the victim of an early-20th century “energy transition” to oil and gas. Despite this rosy story of transition, coal use has never been higher, with countries like Canada, a founding member of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, continuing to open massive new coal mines.

This is the reality that undergirds the story that the world — the West, really — is making “progress” on climate change, a story which typically takes one of two forms. The first manifests as claims that the world’s “current trajectory” for total global heating has improved, from 3.2C by 2100 in 2019 to 2.7C by 2100 in 2024 (with a brief stop, according to some, at 2.5C by 2100 in 2022). This tale of improvement in our “current trajectory” is widespread, but it’s misleading and depends on some troubling assumptions.

First, these claims rely on research with large error bars: the 2.7ºC claim, for example, derives from research that indicates a “likely range (90% prediction interval)” of between 2.1ºC and 3.9ºC, which represent vastly different futures.

Second, the assumptions that ground these projections are both climatic and economic, and while there is some uncertainty in our modeling of the climate system and its sensitivity to greenhouse gases, there is far more uncertainty in the economic modeling of market dynamics and climate policies. None of the projections are guaranteed, and, as noted above, just in 2024, coal consumption set a record, upending projections of a peak issued by the IEA just one year earlier. The IEA now expects coal demand to peak in 2027, which has obvious implications for any claims about warming trajectories.

Finally, these claims are optimistic because they imply that this current trajectory, even if real, is somehow "ok" — an improvement over the worse trajectory we were ostensibly on a few years ago. The reality, as Kemp et al put it in a paper titled “Climate Endgame,” is that "temperatures of more than 2ºC above preindustrial values have not been sustained on Earth's surface since before the Pleistocene Epoch (or more than 2.6 million years ago)." We are entering dangerous and uncharted territory under a path that is frequently cited as reassurance that we are making progress.

The second form that this progress narrative commonly takes is the pernicious insistence that the energy transition is gaining a kind of irreversible momentum, and that an increasingly rapid buildout of wind, solar, and battery capacity will, in spite of the obstinacy of governments, turn the ship around. This narrative is often reflexively bolted on to the end of bad-news stories about developments in the world of climate science — climate communicators use it as a way of “maintaining hope” in their readership. This is also the narrative that liberal climate communicators and the Biden administration lean on when declaring the Inflation Reduction Act the “most significant piece of climate legislation in the history of the United States.”

Unfortunately, while there is truth to the claims that wind and solar are now the cheapest forms of power generation and that there is a massive acceleration in the buildout of wind and solar capacity (driven almost entirely by China), neither of these things necessarily implies an abrupt turnaround and rapid drawdown of greenhouse gas emissions. Brett Christophers argues in his recent book The Price is Wrong that markets are not likely to actually replace fossil fuel use with renewables because, as John Kendall put it in a newsletter on the subject, “what matters [for capital] is not cheapness but profitability.” Fossil fuels are profitable, and they won’t stop being profitable without supply side climate policy raising the costs of production (in one way or another), a direction that remains conspicuously absent from the discussion.

The question of addition vs. substitution is important, too: there is little evidence that an “energy transition” has ever actually happened at a world-system scale. What we’ve seen historically are energy additions (hence coal setting new peaks in 2025!). When it comes to electricity production, we’ve simply added new sources to the mix as they’ve arrived. The idea that adding more and more solar and wind capacity will, through market processes, lead to the substitution of our entire energy supply has no historical analogue, and annual renewable capacity addition has yet to exceed the growth in total energy consumption, meaning that, in very concrete terms, renewables have yet to begin cutting into fossil fuel use.

To make matters worse, as renewables contribute more and more to growing global energy supplies, we’re seeing capital rapidly finding new ways to convert energy production into profit via practices like bitcoin mining in frack fields and the data center boom. As soon as new capacity comes online, new uses emerge to gobble it up.

All of this is to say: things are bad. They’ve been bad the whole time, and have been getting steadily worse, not better, under the guise of a liberal world order committed to “solving” the problem of climate change. A world order led (or dominated) by a series of US administrations that have all claimed to “believe the science.”

A Bipartisan Rejection of Climate Policy

There is a long history of both US failure on and active antagonism to climate policy that spans the entire period during which “climate policy” has been a meaningful benchmark. What I want to focus on here, in brief, is the Obama record (hope and change!) and the longer story of US engagement with international climate negotiations (i.e. Kyoto, Paris, and the COPs between and since).

Obama oversaw the largest expansion of US oil production in history. Obama also oversaw the establishment and entrenchment of the still rapidly growing fracked gas industry and a rise in gas production exceeded only by Trump’s first term (continued, at a slightly more modest growth rate, by Biden). You might say these were market and technological phenomena that had nothing to do with Obama. But in his own view, he played a key role in it: “You know how we became number one in the world in oil production? That was me.” And he played a variety of important roles, including actively pushing fossil fuel industry propaganda, using the language of “clean coal” and calling fracked gas a “bridge fuel.”

This “bridge fuel” lie has since become so mainstream that ENGOs even today, in Canada, are only able to hesitantly suggest that there is a “growing consensus” that methane gas expansion isn’t consistent with climate targets going forward. This was well established in 2012 when Obama cynically spread this message and it’s only become more urgent in the intervening decade and change.

The Obama administration didn’t just support fossil fuel expansion within the US in the name of the Bush-era paradigm of “energy security.” They also directly funded fossil fuel projects abroad.

And they went out of their way to continue the well-established US policy of opposing any sort of binding international climate agreement. In an article for Current Affairs last year, Nathan J. Robinson dug through some of the interviews that were produced as part of the Columbia University oral history project on Obama’s presidency. One of these interviews was with Todd Stern, Obama’s US Special Envoy for Climate Change and the lead negotiator for the US at COP21 in Paris. Stern, following Obama’s direction, held a firm line: “we really didn’t want it to be legally binding, period.” What’s most remarkable is that, according to Stern, virtually everyone else wanted it to be legally binding — “the developing countries” and even “the Europeans.” The Europeans, according to Stern, “were in a very fixed mindset…that it’s got to be legally binding if it’s going to have any teeth to it, any kind of force.”

Obama’s team also attempted to force through a weak agreement at the 2009 Copenhagen Summit (COP15), leading, thanks to a push led by Bolivia, Cuba, and Venezuela, to the accord’s ultimate failure.

The Kyoto Protocol, the last major climate agreement reached prior to Paris, was signed by most countries in 1997. It was legally binding. The US signed in 1998, but treaties in the US need to be ratified by the Senate, and Clinton never asked the Senate to ratify it. The Senate, for their part, made it clear they wouldn’t ratify it, and Bush formally pulled out in 2001.

Even though the US was never a committed party to the Kyoto Protocol, the country managed to play a key role in watering down the Protocol. They pushed through an exemption for military emissions, which to this day are not counted in national emissions inventories. The US military is, among other things, the world’s “largest institutional consumer of fossil fuels,” and this exclusion has left a gaping hole in climate planning. They also successfully lobbied for national emissions inventories to be able to count negative emissions from forests against their total, something countries like Canada have been leaning on for years.

This pattern — of coopting, watering down, and often eventually rejecting international climate commitments — is one that has remained constant across every administration since the founding of the UNFCCC. In his last few months, even genocide Joe — the science-believing hero who brought America back into the Paris Agreement — sent a team of lawyers to the International Court of Justice to argue against the existence of any kind of legal obligations stemming from climate change. The lawyers argued that there is no “right to a healthy environment.”

There’s a much more thorough history to tell here, but the point that I’m trying to make is that the US is no “climate leader,” and it never has been. It is, in fact, the opposite: it is the primary obstacle to just, international coordination on climate change.

The Political Economy of the US Commitment to a Fossil-Fueled World

It should be obvious at this point that the question of whether a given US administration will be “good” on climate change has little to do with their commitment to “science:” they have been universally bad, despite a range of public positions on the question of science. Why they’re all bad is a question that requires a more holistic look at capitalism and US hegemony and empire. I want to make two points here.

First, heavy US investment in and control of oil and gas production, not just in the US but around the world, has shaped American governance and overall political strategy throughout the 20th century and especially after the Second World War. About half of oil and gas globally is produced by state-owned oil companies. Let’s put these state-owned companies to the side, for now, though we’ll return to Saudi Aramco in a minute. US-based companies produce roughly 20% of oil in the world within the US. They also have large holdings around the rest of the world — Exxon Mobil, for example, is the largest corporate owner of Canada’s fossil fuel sector (or was at the time of the linked study). American finance, too, is deeply invested in international fossil fuel production: Canada provides another good example. BlackRock, Capital Group, and FMR LLC, all US-based, were the 4th, 5th, and 7th largest owners of Canada’s fossil fuel industry at the time of that study.

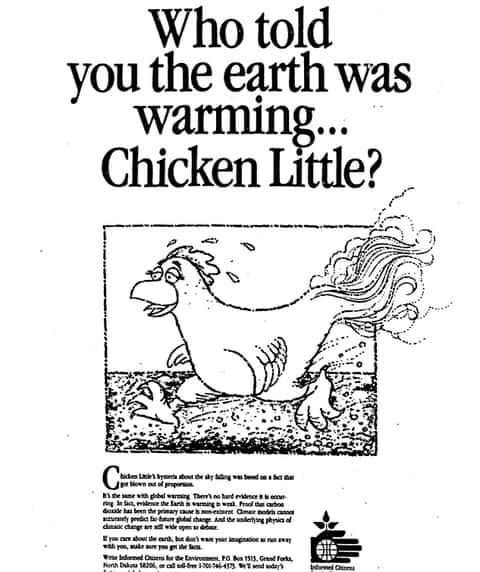

US-based oil companies and financiers have been major players in the global oil industry for over a century, meaning, by corollary, that the global oil industry has been a major player in US political economy for roughly the same period. This has a predictable outcome in a capitalist democracy, and it’s precisely what we’ve seen over the last 40-60 years: the industry and finance capital have done everything they can to prevent policies that would threaten their profits. This has come in many forms, including seeding the politics of climate denial, funding “skeptical” scientists, lobbying, university sponsorships and educational programs, and good old-fashioned revolving-door corruption, to name a few. Climate denial, viewed this way, is a symptom of a historically specific configuration of capitalism; it is a single tool among many, but crucially not itself the principal cause of inaction.

Countries that have large fractions of capital that are deeply exposed, in various ways, to fossil fuels, cannot make meaningful climate commitments without somehow undermining the political power of that fraction of capital — i.e. through a mass-backed movement to expropriate that capital. There is no evidence, at this point, that driving a wedge between green capital and fossil capital in a way that would allow serious climate mitigation to move forward under capitalism is possible, and at least in the US context, there seems to be a close alliance between them rather than a rivalry.

The second issue here is the long entanglement between US imperial power and the global oil economy, an entanglement that took root in the aftermath of World War II. I’ve made this argument in much greater depth elsewhere, so I’ll keep it relatively short here: in the aftermath of World War II, the US linked the development of Europe under the Marshall Plan to its growing control over oil in West Asia, allowing companies like J. D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, a subsidiary of which would become the Arabian American Oil Co. (Aramco) in 1944, to profit and grow along the way. US policy helped to seed a suburbanizing, personal-automobile-obsessed form of economic development in the so-called “free world” as it spread US capital around the world. US power was and continues to be backed by the triad of fossil fuel-dependent development (including, importantly, in agriculture), control of most global oil flows, and the primacy of the US dollar (and its associated “petrodollar” system).

The US role as global hegemon, in other words, is inextricably connected with the fossil fuel economy, and US policymakers understand this. That role is not just important for the state; it’s crucially important for enabling the superprofits American finance capital generates as it pillages the rest of the world. Nobody in power is interested in giving this up. Is a new architecture of US domination built on renewables possible? Perhaps, but there are a number of reasons — again, which I’ve elaborated elsewhere if you’d like to read more — why it may not be, and we can see clearly what those with their hands on the steering wheel think about this. And, of course, a “green” American empire is not a desirable outcome for any number of other reasons.

What Does This Mean for the Climate Movement?

Many climate communicators, activists, and ENGOs — particularly those that style themselves radical — argued during the election that yes, Harris, like Biden, would continue a program of “not enough” when it came to climate change, but that we would have better results fighting Harris through protest and advocacy than we would with Trump. In some superficial ways, I think that’s true: small wins might’ve been possible, and the repression of activists is likely to be worse under Trump, though it’s worth noting that repression of climate activists and, of course, Palestine solidarity activists, under Biden has escalated dramatically. And it’s always worth asking the question, “repression for whom?” Tortuguita, a forest defender in Atlanta fighting the Cop City project, paid the ultimate price, executed by police in their tent. Jessica Reznicek is serving 8 years in federal prison for actions against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Leonard Peltier, an Indigenous activist involved with the American Indian Movement, has been a political prisoner since 1976. Biden has ignored the widespread calls to issue a pardon. (Update: in the last minutes of his presidency, a few hours after I published this, Biden commuted Peltier’s sentence, releasing him from prison — though only to house arrest for the remainder of his life).

The list could, of course, go on.

The key point I’m trying to make here is that Trump’s climate-denial does not represent a break with earlier American politics, it is continuous with it. And his second election, while scary for many reasons, is an opportunity to break with this cycle of reformist cooptation that has allowed us to go the last four decades without meaningful progress on climate mitigation. The climate movement, particularly in “the belly of the beast,” as Che Guevara put it, has to become an opponent of the bipartisan project of American capitalism and empire. We — the climate movement in the imperial core — have to become traitors to this empire. Anything less and we will remain legitimators of the “science-believing” liberal order that has proven unable to reckon with the ecological circumstances it has created.

That means, among other things, a rhetorical turn: we have to be able to say that not only was genocide Joe Biden the butcher of Gaza, but his climate legacy, too, is genocidal. Not only was Obama a war criminal who oversaw the radical expansion of an aerial murder campaign in West Asia, but his climate legacy, too, was genocidal. Not only was Clinton a racist neoliberal that cemented the Reaganite project of dismantling the American welfare state, but his climate legacy, too, was genocidal.

We can’t keep celebrating the small victories, patting liberal “science-believing” administrations on the back for reforms that change nothing; we can’t keep campaigning for a “return to normalcy” after a fascistic, anti-climate interlude of Trump, the AfD, or whoever else. George Jackson, a political prisoner and member of the Black Panthers who was killed by prison guards in 1971, argued in his book Blood in My Eye that the US has been a fascist state since the New Deal, that it was precisely this kind of reformist cooptation of radical movements that saved capitalism in the face of a global revolutionary moment, consolidating it into its modern fascistic form. I’ll unpack this argument in more depth another time, but Jackson aligns closely with the point I’m making here: “It is to our benefit that this person [the president] be openly hostile, despotic, unreasoning,” because both prospective candidates are “merely an extension of the hated ruling corporate class.” If there is no real difference between them when it comes to empire and climate change — if each available electoral choice “is like choosing which way one wishes to die,” or which way one wishes to sentence millions in the global south to die — then we urgently need a strategy that transcends the kind of electoralism we’re presented with.

Let Trump’s second term be the kick in the ass the western climate movement needs to be able to see clearly and abandon the failed project of liberal capitalist reformism. Let us instead join the global movement for a livable future free from the boot of fossil-fueled American domination.

Great stuff from Nick.

I fully agree that the false incrementalism, falsely advertised by the duopolies of Republicans/Democrats and Liberals/Conservatives, promoted falsely through much of mainstream media as 'progress' and 'change', is a colossal scam that will go down in the pages of human history as the crimes of the century.

Further, Nick correctly identifies a cornerstone of this planned failure - "each available electoral choice “is like choosing which way one wishes to die,” or which way one wishes to sentence millions in the global south to die".

As well, Nick accurately describes the nature of this institutional political-economic corruption as being fascistic. That is to say, corporations have attained a unity with politics that has provided them with privileged anti-democratic power that determines, in advance, that decades of elections have been a scam of democracy and constructive climate initiatives. The secrecy of this corporate-government inner power circle is a grave threat not just to democracy, but planetary well being and human happiness.

Thanks Nick - you nailed it again!

Wow - powerful analysis powerfully presented!